If pure mathematics is a language, then numbers and variables constitute letters, definitions constitute words, and theorems constitute short paragraphs, all building up to a unified story that explains the explanation for the world. What is its grammar? Logic.

Definition 1. A proposition is a sentence that is either true, denoted , or not, denoted

, but not both. A true proposition

is called a theorem. We will always make the following notations:

This is technically known as the law of excluded middle, which agrees with our intuition of truth. We will use this starting point for further discussion.

It helps us at times to make the abbreviation , called false. These are called truth values. This gives us the following definition for the negation.

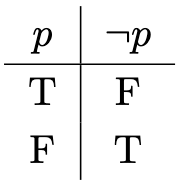

Definition 2. The negation is defined as follows:

To condense our definitions, we can use a truth table:

This gives us the following observation by repeated uses of said notation:

.

More generally, we can discuss logic from an algebraic lens.

Definition 3. A propositional variable is a placeholder that takes on exactly one of the truth values

or

.

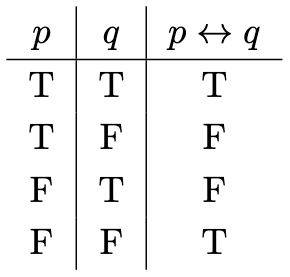

We want to discuss the truth values of two propositional variables . To do that, we need to define the biconditional.

Definition 4. Define the biconditional using the following truth table:

For any propositional variable and any propositional variable

defined in terms of

, we write

if

is a theorem for any substitution of

.

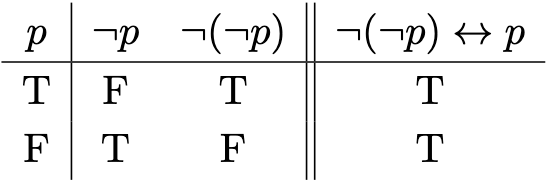

Theorem 1. Let be a propositional variable. Then

.

Proof. We use the following truth table argument:

Many a time, we want to treat theorems as propositional variables. Propositions formed using existing propositions are known as compound statements. We can formalise this using tautologies, with their negations being contradictions.

Definition 5. A compound statement is a tautology if

is a theorem regardless of substitution of truth values.

With this vocabulary, for any compound statement and any compound statement

defined in terms of

, we write

to mean that

.

A corollary is a theorem that, for readability purposes, is a straightforward consequence of a previously established theorem.

Corollary 1. For any propositional variable ,

.

A compound statement is a contradiction if

for some tautology

.

Corollary 2. Let be a tautology and

be a contradiction. Then

is always false, and

.

Based on the starting points and

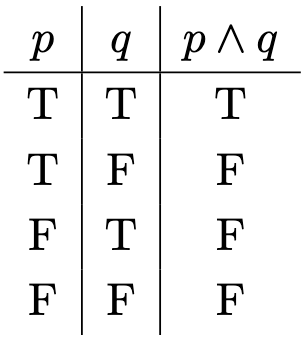

, we can define many logical connectors. One crucial one is known as the conjunction.

Definition 6. Define the conjunction using the following truth table:

The conjunction has many useful properties. But first, we need to establish some results pertaining tautologies and contradictions. These will be lemmas—theorems that, for readability sake, are intermediate steps to prove more significant theorems.

Lemma 1. Let be any propositional variable. Then

Proof. Use a truth table argument.

We want to eventually prove propositions such as . However, we first need to prove that we can chain equalities, i.e. that

and

implies

.

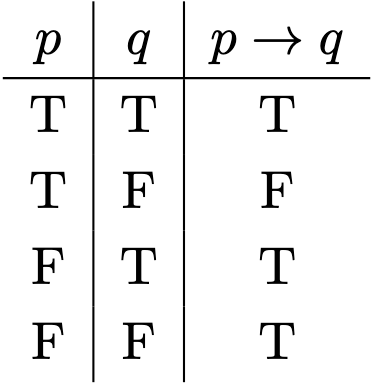

Definition 7. Define the implication using the following truth table:

To prove our famous results, we need lemmas, which are theorems that, for readability purposes again, are intermediate steps required to prove a theorem.

Lemma 2. For any propositional variable ,

Proof. Use a truth table argument.

Our next lemma requires us to chain equalities of propositional variables. This helps us prove the commutativity of conjunction.

Lemma 3. For propositional variables ,

Proof. We remark that for any substitution of truth values into , if

, then

automatically. Thus, we will suppose that . By definition of the truth value of the conjunction, we have

and

.

- Substituting

with

,

and

.

- Substituting

with

,

and

.

Therefore, , as required.

Finally, we can prove the commutativity and associativity property of conjunction.

Theorem 2. Let be propositional variables. Then the following hold.

Proof. For the first result, use a truth table argument. For the second result, when we substitute with

, we have

with respect to

, so that by chaining equalities,

We get the same result when substituting with

.

There is more to say about propositional logic, such as disjunctions and even argument forms, but this post is getting as long as it needs to. Crucially, we have implemented the core elements of propositional logic which we can take advantage of in future topics.

—Joel Kindiak, 15 Nov 24, 2359H

Leave a comment