In the previous post, we introduced what we mean by logic, which agrees largely with our intuitive process of making sense of the world. We defined truth values, negations, and conjunctions. The parallel to the conjunction is the disjunction, defined as follows.

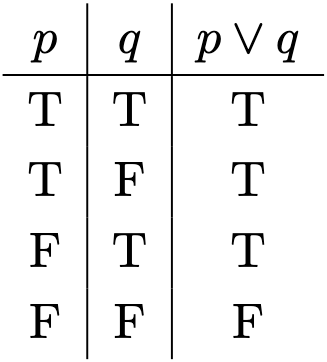

Definition 1. Define the disjunction using the truth table:

We can verify that and

, just like conjunction.

The disjunction share many properties with the conjunction. In fact, one key result that connects (pun intended) all three connectives is de Morgan’s laws.

Theorem 1 (de Morgan’s Laws). Let be propositional variables. Then

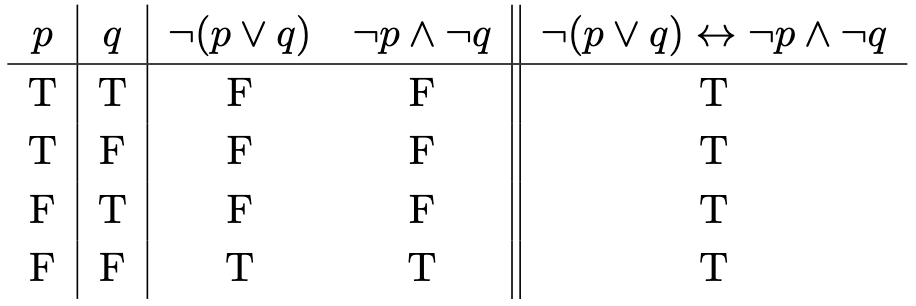

Proof. For the first property, we use the following truth table argument:

For the second property, we apply the first property but replace with

and

with

, then apply the double negative property, to obtain

Negating both sides and applying the double negative property again,

These automatically yield the disjunction properties.

Corollary 1. Let be propositional variables. Then the following hold.

Proof. We illustrate the proof of the first property. Applying double negatives, de Morgan’s laws, and commutativity of ,

The second property follows similarly.

The conjunction and disjunction connectors distribute (i.e. split) over each other.

Theorem 2. Let be propositional variables. Then

Proof. For the first property, observe that the results hold for and

, so that it holds in general. The second property follows from the first using the double-negation-cum-de-Morgan trick in Corollary 1.

The disjunction is intimately connected to the implication, and has massive implications in studying logic, pun intended.

Theorem 3. Let be propositional variables. The following hold:

Proof. One can the first result by substituting and

respectively, and derive the second result using de Morgan’s laws.

These results affords us an incredibly powerful result, which is to chain logical implications with one another.

Theorem 4. Let be propositional variables. Then

To abbreviate, we assume the following order of operations when parentheses are omitted in descending priority: .

Proof. Applying the various logical properties,

Can we chain biconditionals? That is, if and

, is it true that

? Intuitively, yes! Rigorously, how do we prove it? We need several lemmas.

Lemma 1. For propositional variables ,

Proof. For the first result, first verify that and

. Then substituting

and

respectively yields

For the second result (i.e. the second ), write the implication as a disjunction

, then distribute the logical connectives (in the usual manner) to obtain

Here, we used the results and

.

Lemma 2. For propositional variables ,

Proof. Writing the implication as a disjunction,

With these tools in place, we can now prove our main result for the biconditional.

Theorem 5. Let be propositional variables. Then

Proof. Unraveling the previous lemmas,

Why did we care about logic? We have completed what amounts to verification of various truth values, given certain combinations of propositional variables. We even derived several useful tautologies. These tautologies form the bedrock of proof techniques, which are the ligaments of mathematics. We discuss this next time.

—Joel Kindiak, 16 Nov 24, 2034H

Leave a comment