Let’s properly discuss classical trigonometry. For a novel approach using rational trigonometry, see this post. Assume that the notion of an angle is well-defined.

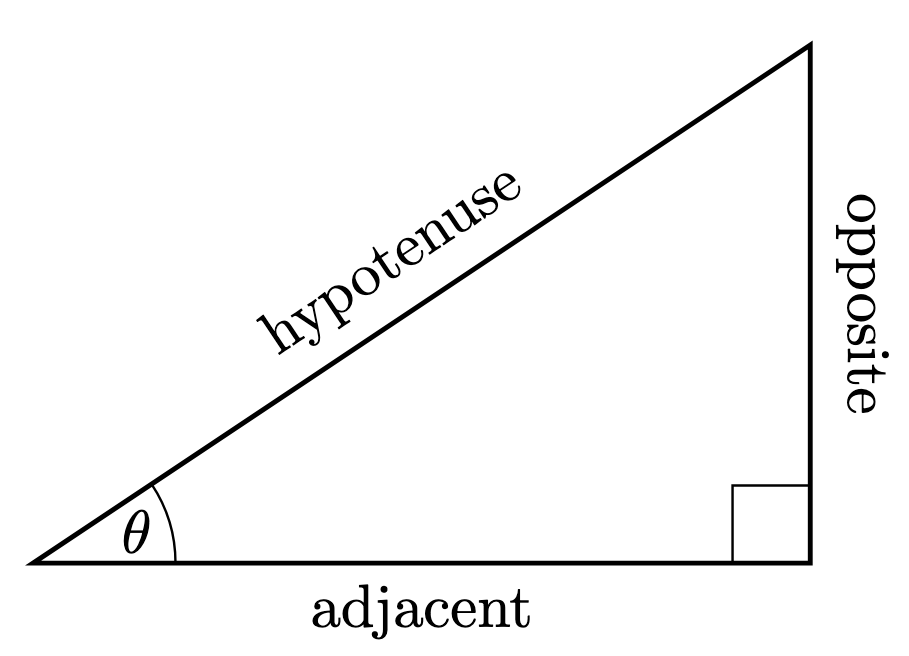

Definition 1. Consider the following right-angled triangle with acute angle . Here and subsequently, we adopt the radian notation for angles that stipulates

.

We abbreviate the words opposite, adjacent, and hypotenuse. We define the sine, cosine, and tangent of as follows:

Example 1. By considering the –

–

and

–

–

right triangles, we have the following trigonometric ratios for special angles:

The case will play a crucial role for us later. Denote

for brevity. We will not care too much about the tangent function, since it is connected to sine and cosine in the following way:

Theorem 1. Let . Then

Proof. For the first identity, use Pythagoras’ theorem to obtain

For the second identity, we observe that

For the last identity, since the complementary angle is ,

Strictly speaking, the cosine function is effectively a mutation of the sine function, and so we could technically do all of trigonometry in terms of sine. However, cosine does have its uses and will play a crucial role in our discussions moving forward.

There are many trigonometric identities built off the first two identities, and we will leave them as exercises in algebraic manipulation. For a serious study of trigonometry, we have to ask the all-important question: what is if

is not acute? In particular, what is a sensible definition for

? The answer to the latter question turns out to answer the former question.

Theorem 2. Let be acute angles. If

is acute, then

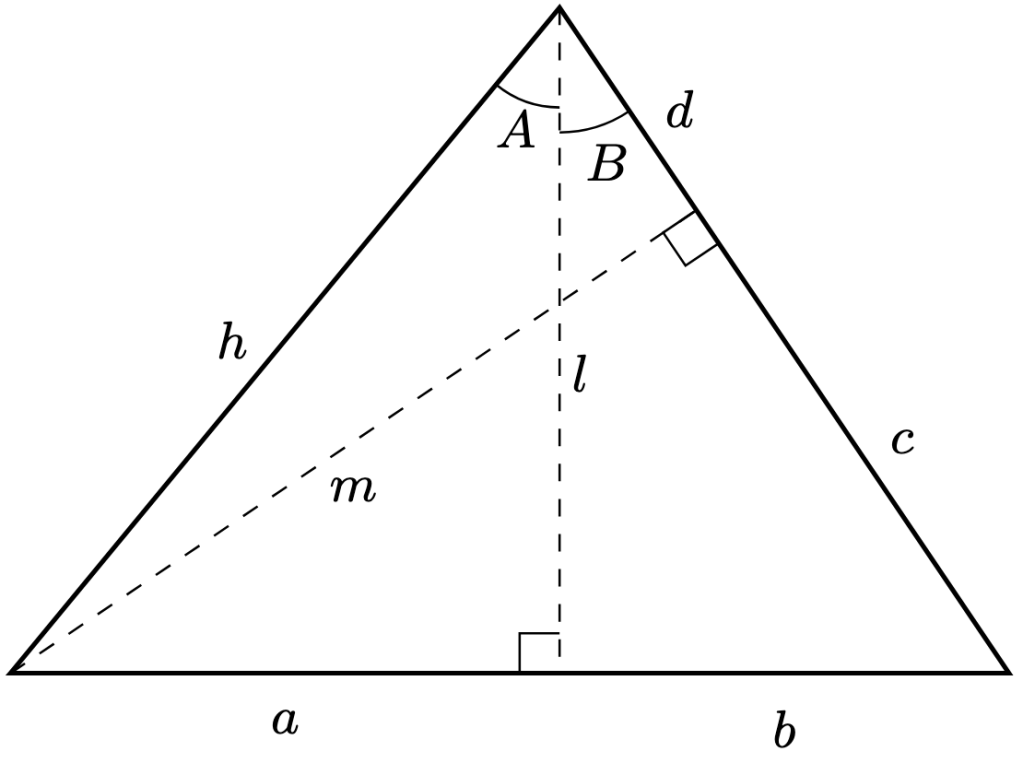

Proof. Consider the following diagram for the proof of both identities.

The first identity corresponds to finding an alternate expression for , and the second identity corresponds to finding an alternate expression for

. The ratios of interest are

By considering the area of the whole triangle using the bases and

respectively,

Dividing by on both sides,

By basic trigonometric ratios,

For the second identity, by the Pythagorean theorem,

By algebruh,

Therefore,

Simplifying the equation,

By Pythagoras’ theorem, , so that

Dividing by on both sides,

By basic trigonometric ratios,

Corollary 1. Let be acute. If

is acute, then

Proof. Set in Theorem 2.

The key insight is the following: as long as the right-hand side is well-defined, so is the left-hand side. This is our strategy to define and

on all of

. Let’s systematise our plan.

Definition 1. For any subset , let

be the proposition that for any

,

and

are well-defined, and

Write to abbreviate the proposition “

is true”. Our overarching goal is to provide sensible definitions for

and

such that

. By Theorem 1, we have established

and Corollary 1 will help us “double” our results to achieve the massive sub-goal of

.

Theorem 3. For any , suppose

and

are well-defined on

. For any

, denote

and define

If , then

.

Proof. Fix . Then

. Observe that

so that and

Since , expanding the right-hand side yields

On the other hand,

With careful algebraic expansion, we will obtain

Similarly, we will obtain

Corollary 2. . In particular, we have the following special angles:

Proof. Fix . Then there exists

such that

. Using induction, we can prove that

. Therefore,

are well-defined on

and the identities

hold for any . Hence,

, as required.

Corollary 3. For any ,

Furthermore, for any positive integer ,

We have done a remarkable task: defining on

and proving that they satisfy the desired addition formulae. But we haven’t proven this case for all of

, since

. Surprisingly, though, Corollary 3 gives us a unique insight. Observe that for

,

and

are well-defined expressions. This means we can do a “reverse” definition for non-positive

.

Theorem 4. For any , let

denote any integer such that

. The notions

are well-defined by Corollary 3. Then . In particular,

Proof. Fix . Find

such that

and

. Then

so that

allows

A similar calculation yields

Thus, we have properly defined and

on all of

, and even proved that the identities

are well-defined and hold for any . From these two key identities, we obtain all other trigonometric identities commonly obtained in tables of mathematical formulas.

—Joel Kindiak, 4 Jun 25, 1758H

Leave a comment