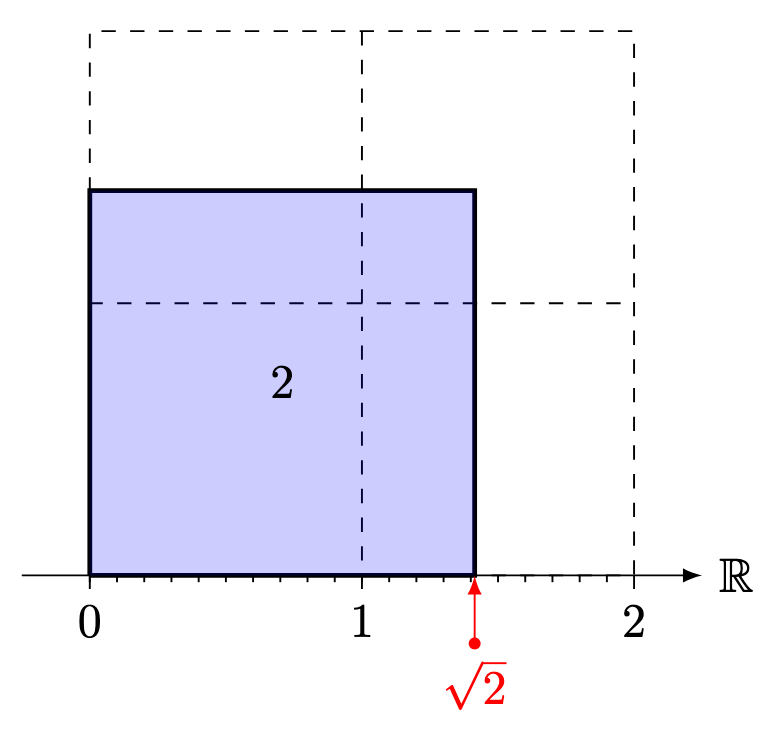

The number line helps us picture positive numbers, negative numbers, and even any point in between: we call these points real numbers, and represent them using the symbol :

All familiar numbers belong on this line:

- Natural numbers:

- Integers:

- Fractions:

- Negative fractions:

A number is called a rational number if it is either or a fraction or a negative fraction. Other numbers like

or

are also real numbers that are not rational numbers:

calculates the length of the circumference of a circle with unit radius.

calculates the length of the diagonal of a unit square.

Using this point of view (pun intended) we can accept these rules for adding real numbers:

When positive, real numbers can also be used to describe areas.

Each positive real number length matches a rectangle with base

and height

. If

, the rectangle becomes a line, which has

area, giving the trivial equations

We can therefore use different rectangles with the same area to recover many correct equations.

In particular, we obtain the following area properties for positive real numbers:

- Commutativity:

- Multiplicative identity:

Furthermore, we can use different rectangles with the same area to construct different real numbers. For example, we can use a square with area to construct the real number

.

Likewise, we can use a square with area to construct the real number approximately equal to

, which we represent using the symbol

.

Remark 1. We will revisit this example when discussing geometry.

For this reason, we call this number the “square root” of : it is the root number, that when used to construct a square, produces a square with area

. Replacing

with any positive number

,

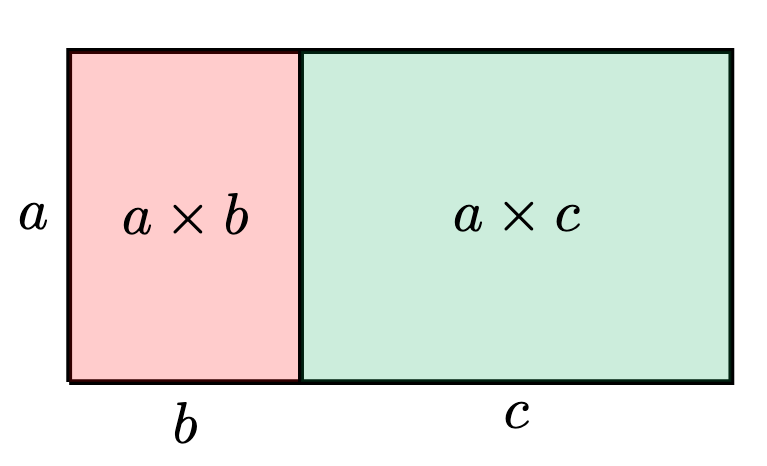

Write to mean the area of the rectangle with height

and base

:

Since the two smaller rectangles combine into a larger rectangle with height and base

, we recover the “rainbow method” to expand expressions (i.e. distributivity):

where the second identity follows from the first:

Example 1. Evaluate . In particular, evaluate

.

Solution. By using the “rainbow method”,

Setting and

,

Remark 2. Many students will sadly make the rookie mistake .

Example 2. Explain why it is not true in general that .

Solution. Consider the case and

. Then

We call this violation of a proposed general pattern a counterexample.

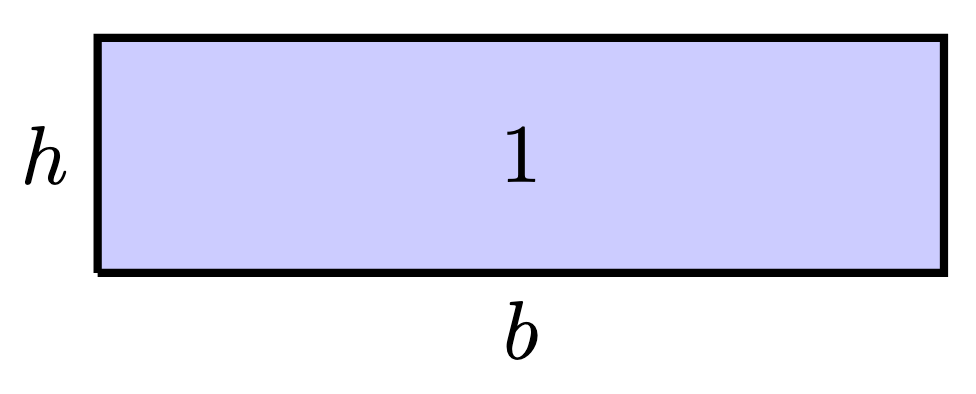

We can do better. Consider the rectangle below with base , height

, and area

.

Since there is only one rectangle with base and area

, there is exactly one positive number

such that

We define , and inverse property:

Hence, we define real number division by

Remark 3. If , then no matter what height

we have, the area of the corresponding rectangle will be

. Hence, the quantity

is undefined. In other words: division by

is illegal.

Example 3. Given , show that

.

Solution. Using real number division,

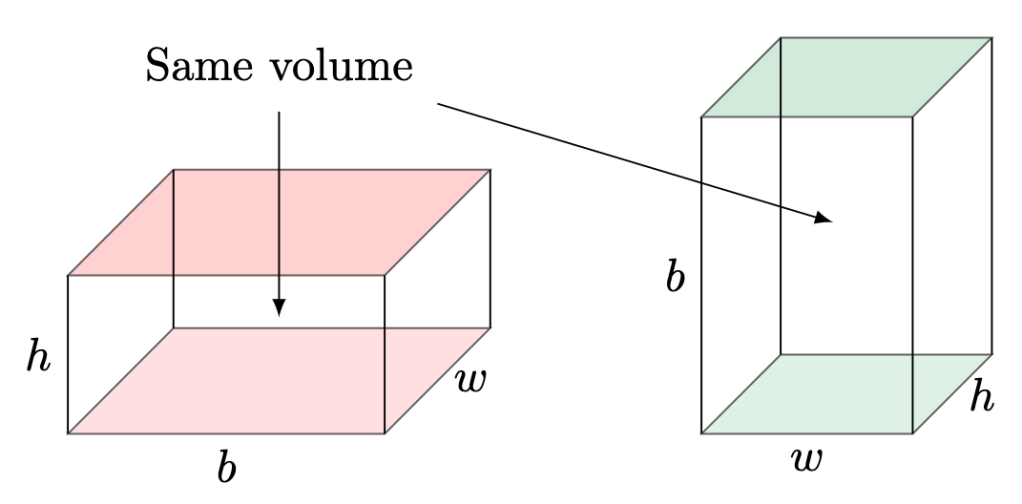

If we want to multiply many times, we can bump things up by one dimension. Consider the volume of a cuboid with base , width

, and height

.

Since both cuboids have the same volume, we can multiply in either order (i.e. associativity):

Hence, we can define three-way multiplication by

without confusion. For products of even more numbers, though we would find it difficult to imagine objects beyond volume, we don’t need to worry:

Example 4. Given , show that

. In particular,

Solution. Since we can multiply in any order of “brackets”,

Corollary 1. Given ,

Proof. Using Example 4,

To add two fractions, use Example 3:

Remark 4. By the principle in Remark 3, you might think that the number is also undefined. After all, how can a rectangle have negative base length? That is because we are using areas as an analogy to describe real number calculations. Nevertheless, the quantity

is still well defined; indeed, using Corollary 1,

and is a clearly well-defined positive fraction, so that

is a perfectly well-defined rational number. However, trying to define

will create problems:

implies that

which is absurd. Therefore, remains undefined:

Division by zero is (generally) illegal.

Corollary 2. Given ,

Proof. Recall that :

Recall the definition

Hence, use Corollary 1 to deduce that

Numbers mean nothing unless we can perform meaningful calculations with them. To add two fractions, we first find their (lowest) common denominator, then add them normally.

Example 5. Evaluate without a calculator.

Solution. By using the common denominator and Corollary 1,

Example 6. Evaluate without a calculator.

Solution. Following Example 5 but instead using and Corollary 2,

Example 7. Explain why it is not always true that .

Solution. Consider the case and

. Then

Oddly enough, we have derived the important main ideas for calculating using real numbers, so we can extend these ideas to discuss basic algebraic manipulations in the next post.

What remains are some technical remarks about our discussions.

Remark 5. It turns out that for any non-zero real number ,

is always not true (i.e. false)! Similarly, if and

, then the statement

is always false.

Remark 6. We have built the basics of real number calculations, and since we will use the letters and

soon, it gets very messy to write

. To simplify our work, we write

, so that the “rainbow method” looks like

In particular, Example 1 looks like the following:

Sometimes, we use a dot to to clarify that we are doing multiplication:

Hence, we have the identities

Without brackets, we will always multiply before adding:

leading to the usual PEMDAS rule:

- parentheses (or brackets),

- exponents (e.g.

),

- multiplication / division,

- and finally addition / subtraction.

In fact, division is defined using multiplication:

Likewise, subtraction is defined using addition:

Remark 7. To properly construct the real numbers, beyond the rectangle-area picture, takes a lot more effort. We first need to define the rational numbers, then the real numbers, and finally for completeness, the complex numbers.

—Joel Kindiak, 23 Sept 25, 1556H

Leave a comment