Here’s our question today: what is the sum of angles in a triangle?

Previously, we have seen how linear equations can represent lines. If

, then

so that the line has gradient and

-intercept

.

- If

, then

. In this case, if

, then

, and the line is vertical with

-intercept

.

We can make a few more basic observations about our lines below, properly constructed here, which uses many tools from linear algebra.

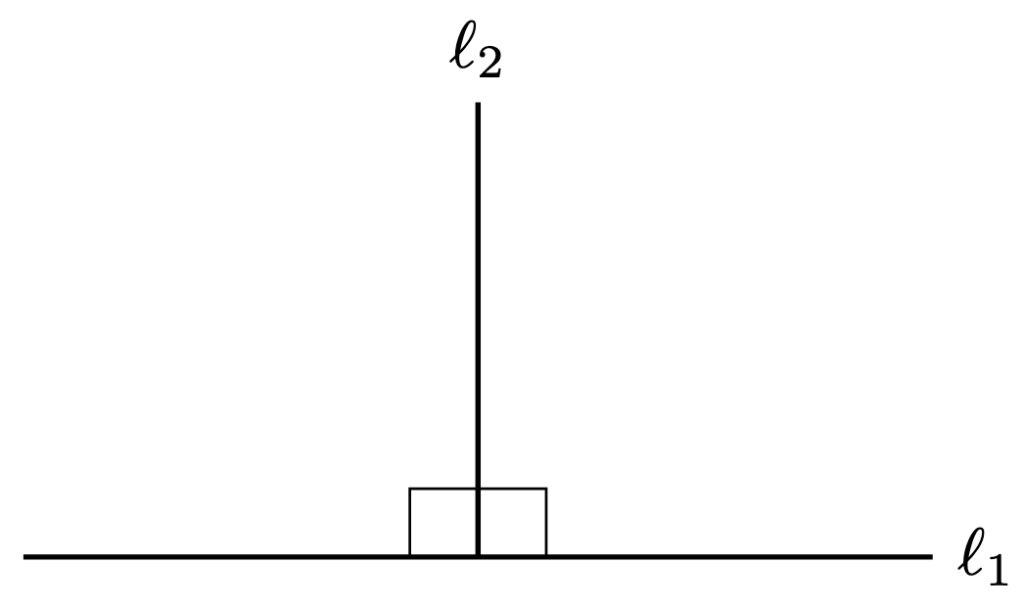

Firstly, we use the word “angle” to describe the amount of separation between two lines. The simplest case occurs when the two lines are at right angles (i.e. ortho-gonal) to each other. We use the symbol to denote angles that are right, and in this case write

:

By convention, we declare one right angle to equal (i.e.

degrees), so that the sum of adjacent non-overlapping angles on a straight line add up to

.

Definition 1. An angle is said to be

- right if

,

- acute if

(i.e. smaller than a right angle),

- obtuse if

(i.e. larger than a right angle).

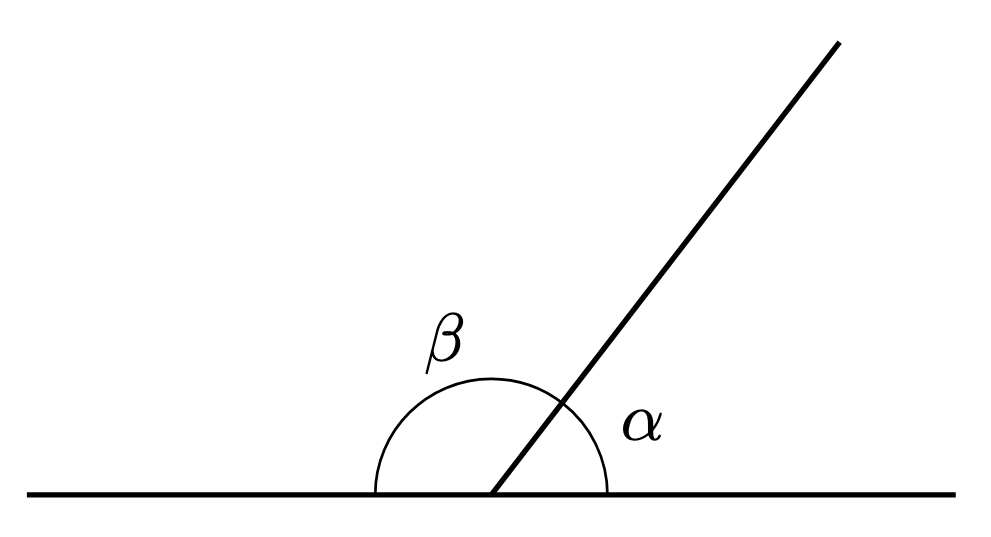

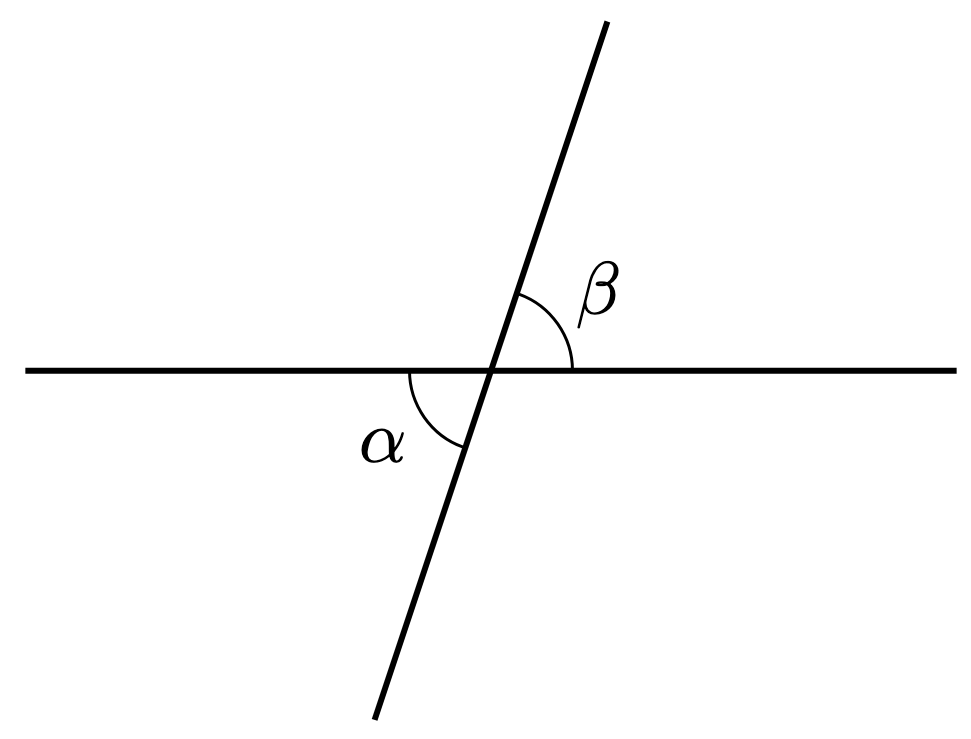

For example, the angle in the diagram below is acute, while the angle

is obtuse.

Eventually, we will consider angles that are reflex (i.e. if ).

Remark 1. Usually, the Greek letter ‘theta’ denotes an angle. When there are multiple angles, we use the Greek letters ‘alpha’

, ‘beta’

, ‘gamma’

, and so on.

Remark 2. We can formalise the idea of angles using calculus (i.e. the study of rates of change), discussed elsewhere. The choice of the number has a rich human history, and its use is strengthened by its factors

.

Consider two lines :

- We call two non-identical lines

parallel if they don’t intersect and write

.

- In this case, we will use the decorations

,

, etc to denote parallel lines.

- We call the pair of angles

a pair of interior angles if

.

We make the key observation that assuming a flat screen, if and only if any pair of interior angles sum to

. This result is known as the parallel postulate in Euclidean geometry.

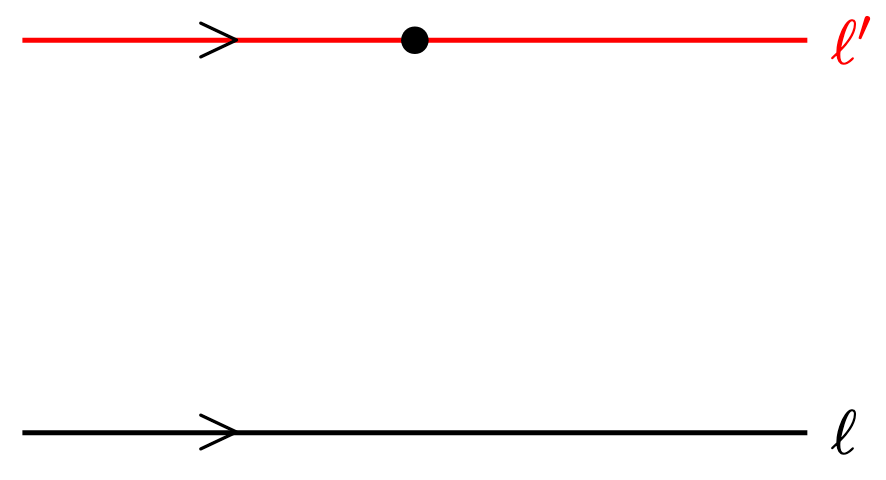

We can also use our construction to conclude Playfair’s axiom:

Lemma 1 (Playfair’s Axiom). Let be a line and

be a point that does not lie on

. Then there exists a unique line

that passes through

and is parallel to

.

Proof. See this post.

Going forward, we will take advantage of these basic observations to derive several foundational tools for geometric inference, and resolve the sum-of-angles question that we started with.

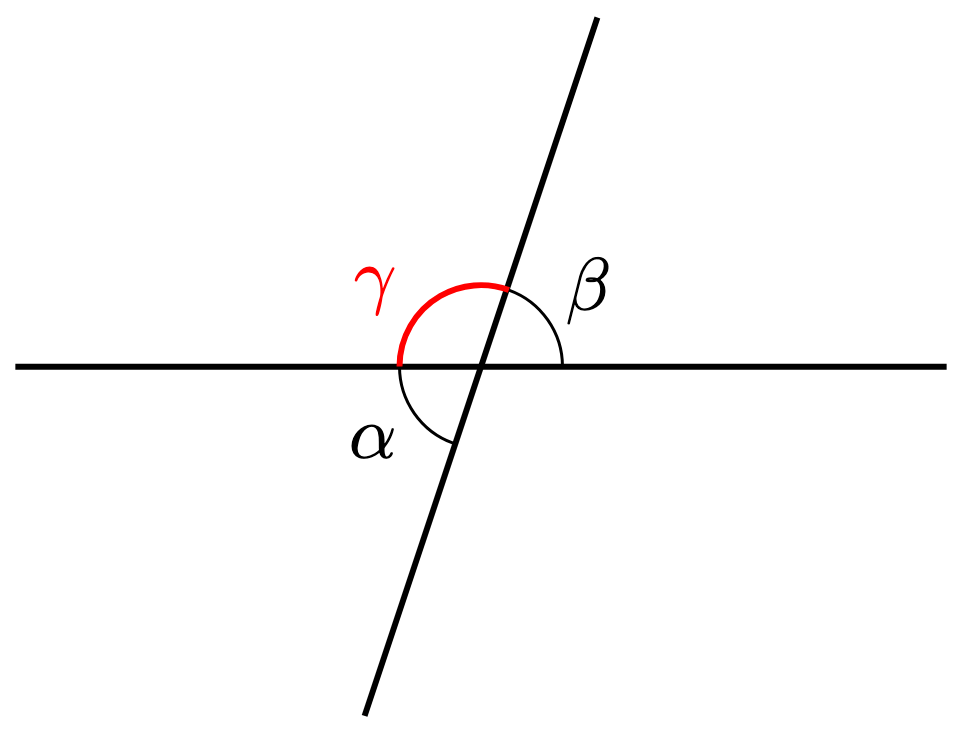

Theorem 1. Given two non-parallel lines, the vertically opposite angles are equal to each other.

Proof. Construct the angle below.

Since adjacent non-overlapping angles on a straight line sum to ,

Therefore, since we can cancel the term on both sides (this is called the cancellation law),

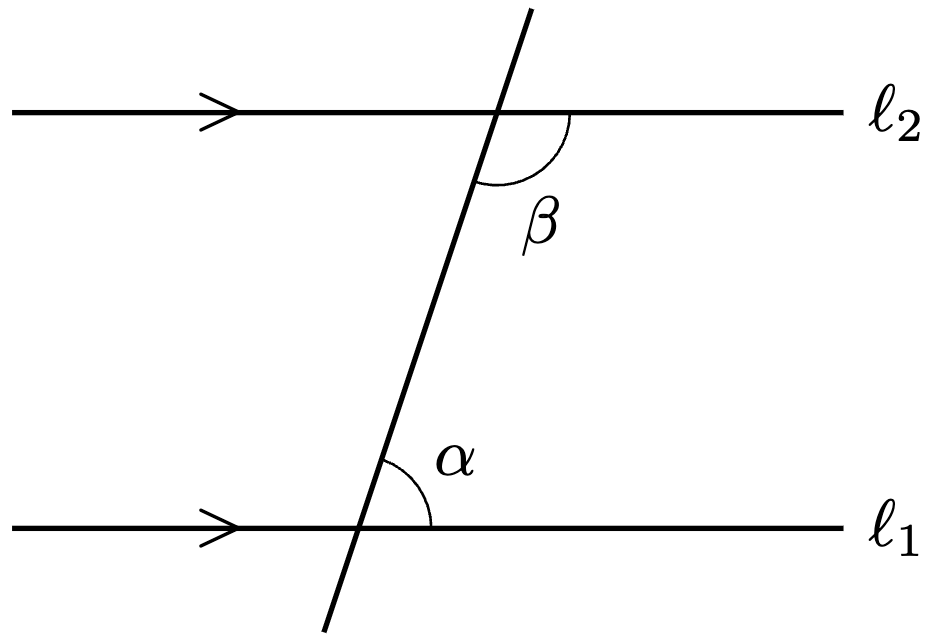

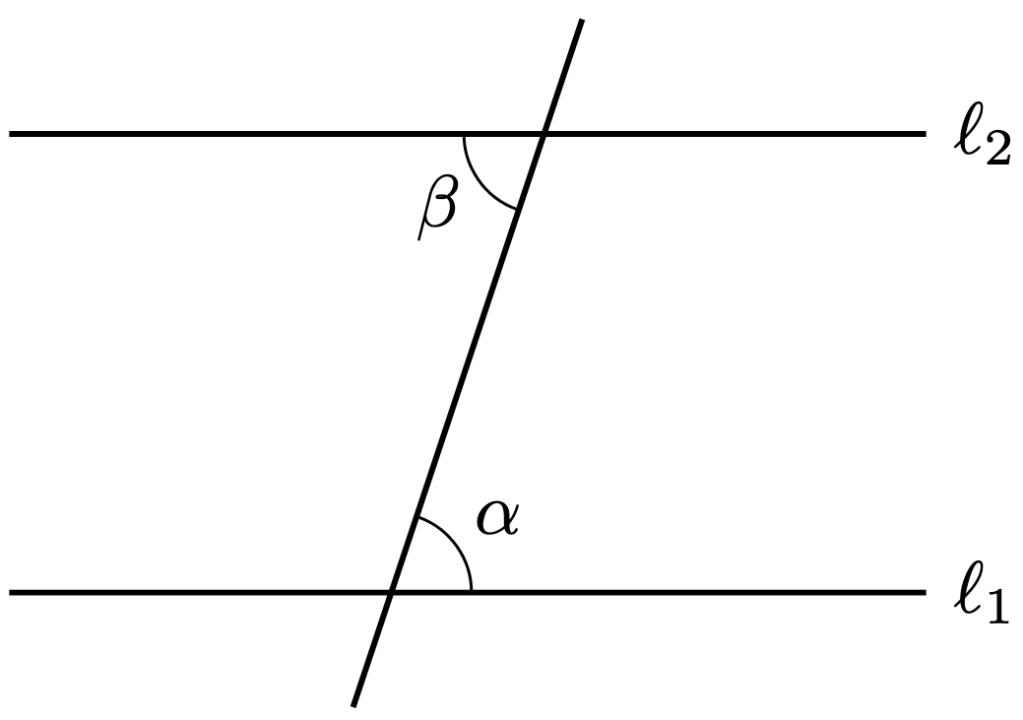

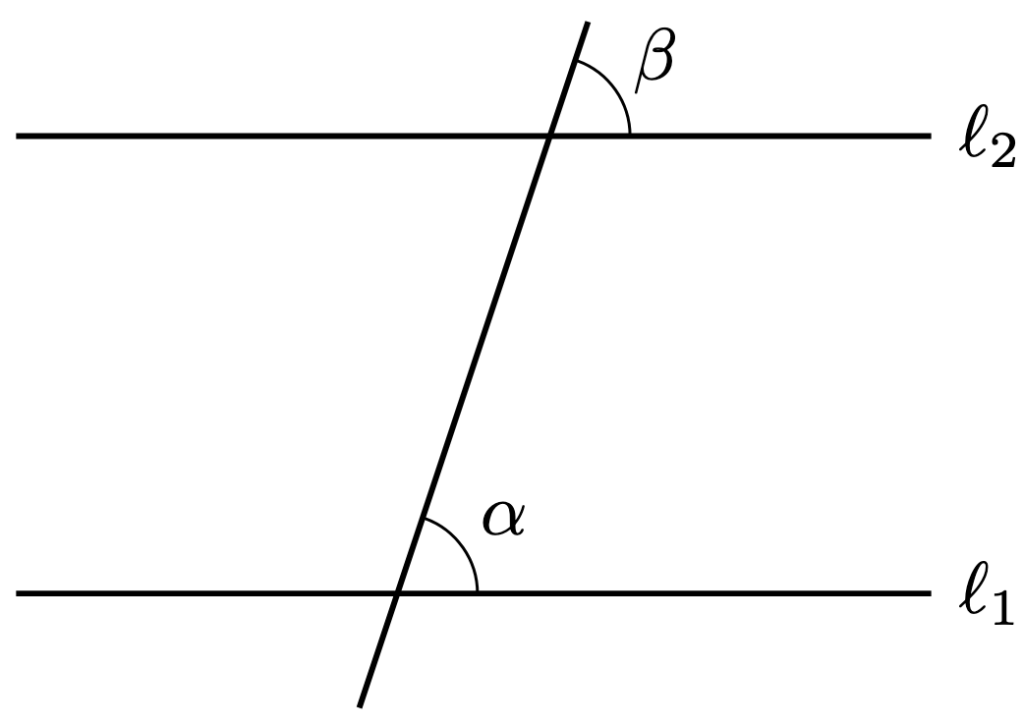

Theorem 2. The two lines below are parallel if and only if the alternate angles

are equal to each other.

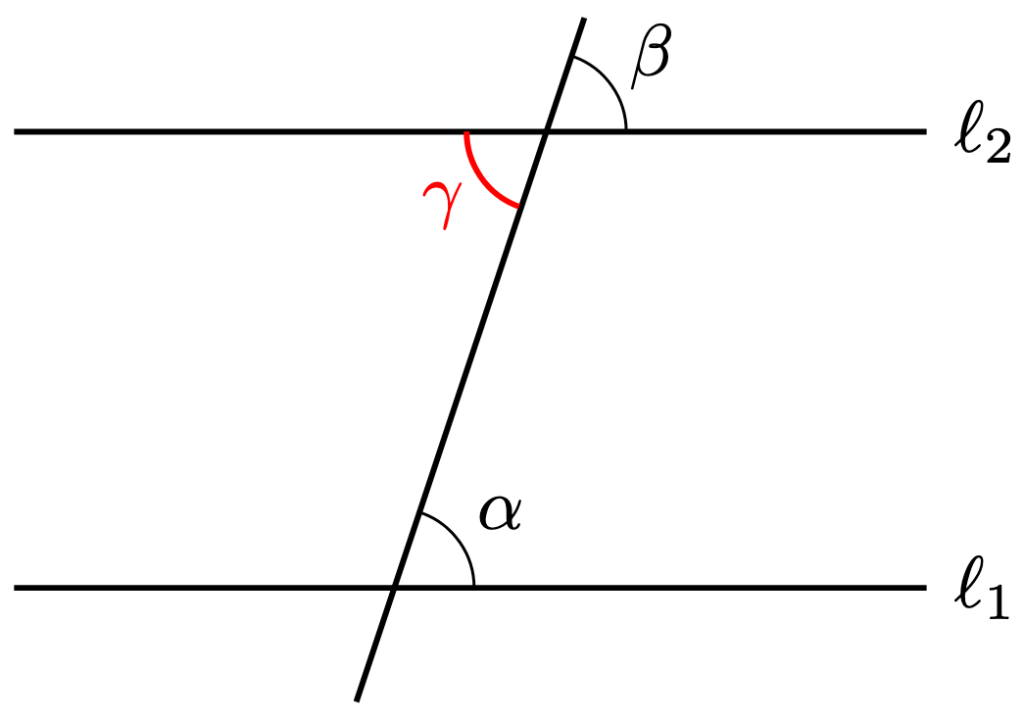

Proof. Construct the angle below.

Since adjacent non-overlapping angles on a straight line sum to ,

By the parallel postulate,

Using the cancellation law in Theorem 1,

Theorem 3. The two lines below are parallel if and only if the corresponding angles

are equal to each other.

Proof. Construct the angle below.

Then are vertically opposite. By Theorem 1,

Furthermore, are alternate angles. By Theorem 2,

Remark 2. In most school problems, you would be hand-given the parallel lines , and then, if needed, prove the angle equality result (e.g.

). You can use the following presentation for school assessments (e.g. homework, tests, examinations, etc):

At least, this working got me full credit when I was a secondary school student.

Theorem 4. The angles in a triangle sum to .

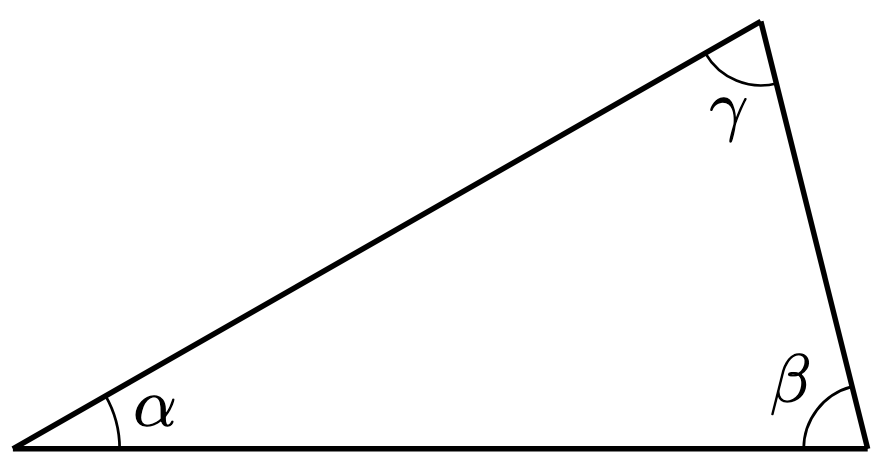

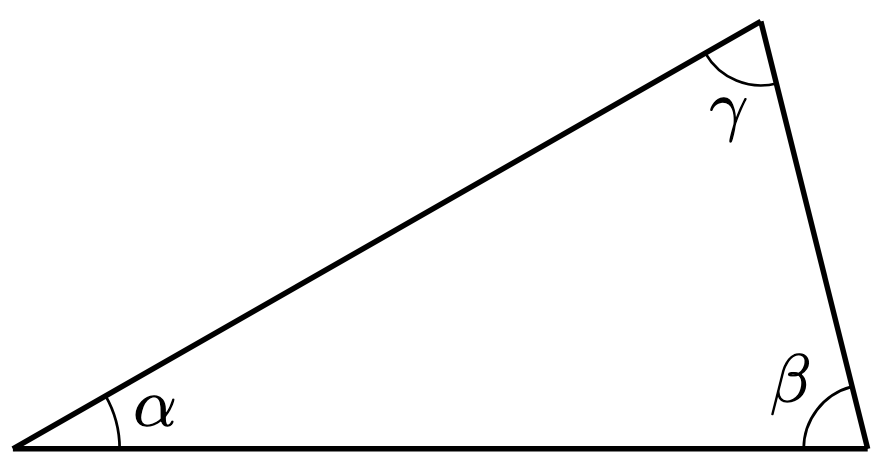

Proof. Consider the triangle below without loss of generality.

We need to prove that .

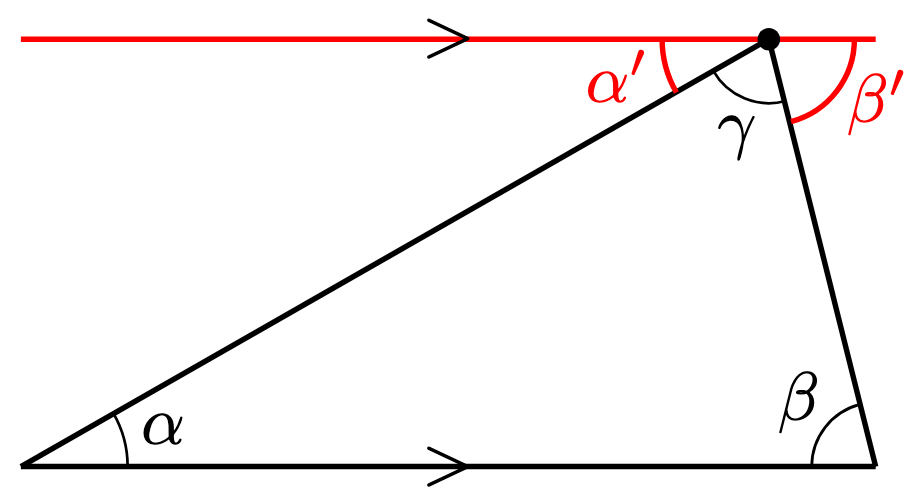

Use Playfair’s axiom to construct a line parallel to the base

of the triangle that passes through the opposite point (i.e. vertex) of the triangle:

Construct the angles and

.

Since are non-overlapping adjacent angles on a straight line,

We also observe that and

are pairs of alternate angles. Since

, by Theorem 2,

Therefore, using the usual rules of addition,

While there are many results that can and should be proven using these basic results, we will delay them to connect their usefulness with other geometric objects. For example:

- The fact that a triangle is isosceles if and only if its base angles are equal is a consequence of our discussion on congruent triangles.

- Two angles in the same segment in a circle must equal each other, and we will explore this idea when considering circles in more depth.

Rather than explore these results all in one post, we will smatter them throughout our discussion in connection with other parts of geometry.

For now, we will use Theorem 4 to prove one of the most important results in secondary school (and hence higher-level) mathematics—Pythagoras’ theorem.

—Joel Kindiak, 6 Oct 25, 2100H

Leave a comment