Pythagoras’ theorem is the most important idea in geometry, all of mathematics even. But before discussing it, let’s ask a simple question.

Given a unit length , and a positive number

, how can we construct

?

Recall that means that

. We can achieve this construction goal using Pythagoras’ theorem.

(A proper construction, as with many other geometric ideas, relies on real analysis.)

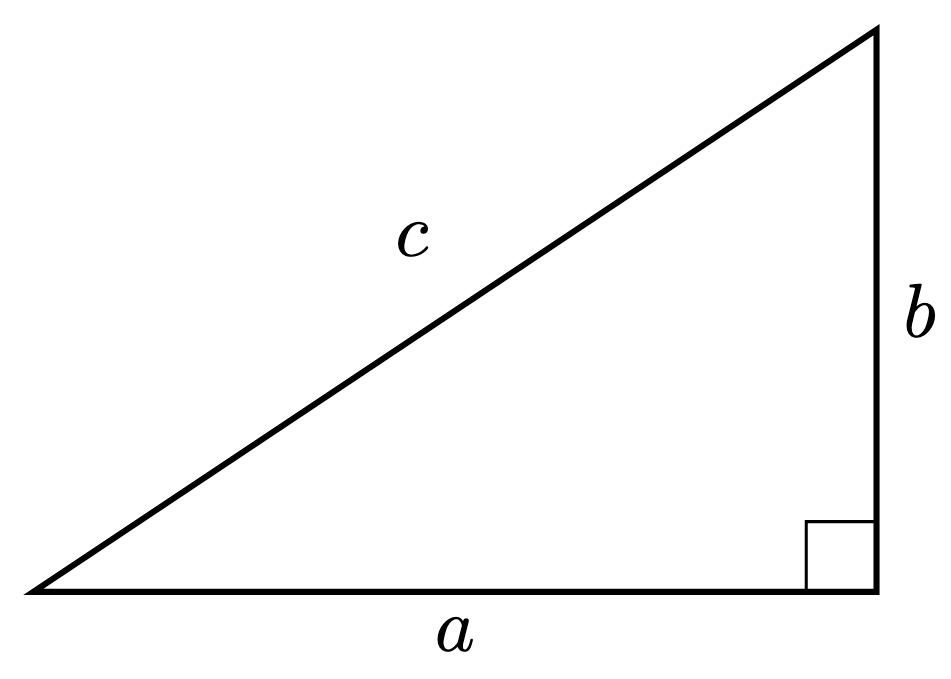

Theorem 1 (Pythagoras’ Theorem). Given a right-angled triangle below,

We call the longest side with length the hypotenuse of the triangle.

If are positive integers, we call

a Pythagorean triple. The most famous such example would be the

–

–

triple:

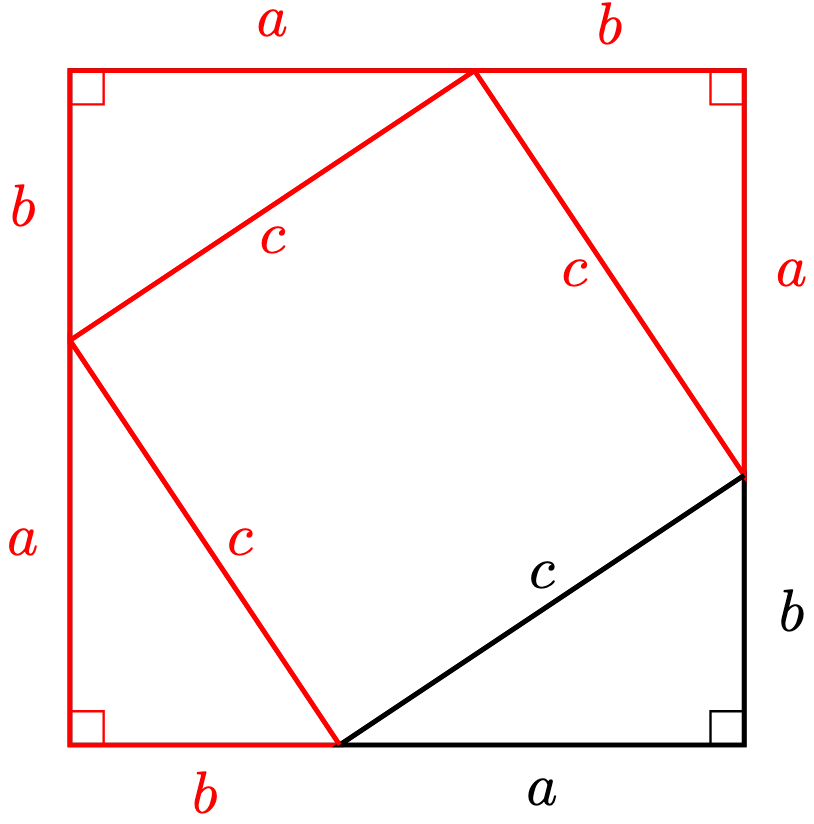

Proof. Draw three extra identical triangles, so that we get a large square with side length .

We claim that the slanted four-sided shape (i.e. a quadrilateral) in the middle is indeed a square.

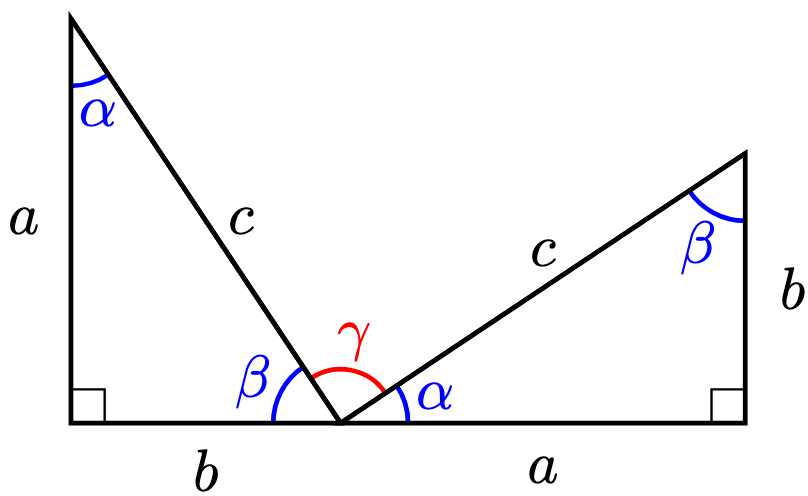

Since the right-angled triangles are identical, we take two adjacent triangles and label their angles as follows.

We want to prove that . Since the angles in the centre are non-overlapping adjacent angles on a straight line,

On the other hand, since the angles in a triangle sum to ,

Therefore, using usual calculations,

Since the hypotenuses are all equal, we know that the quadrilateral has four equal sides. Hence, we have a square in the middle whose area is , so that

There are many applications of Pythagoras theorem that, in my humble opinion, are not worth discussing outside a tuition class. Yet, Pythagoras’ theorem can resolve for us a simple yet non-trivial question: what is a circle?

You might say, “a circle is a non-straight bendy or curvy line that closes in on itself”. This formulation is valid when formalised in the language of algebraic topology and homology theory.

Let’s keep things simple for now.

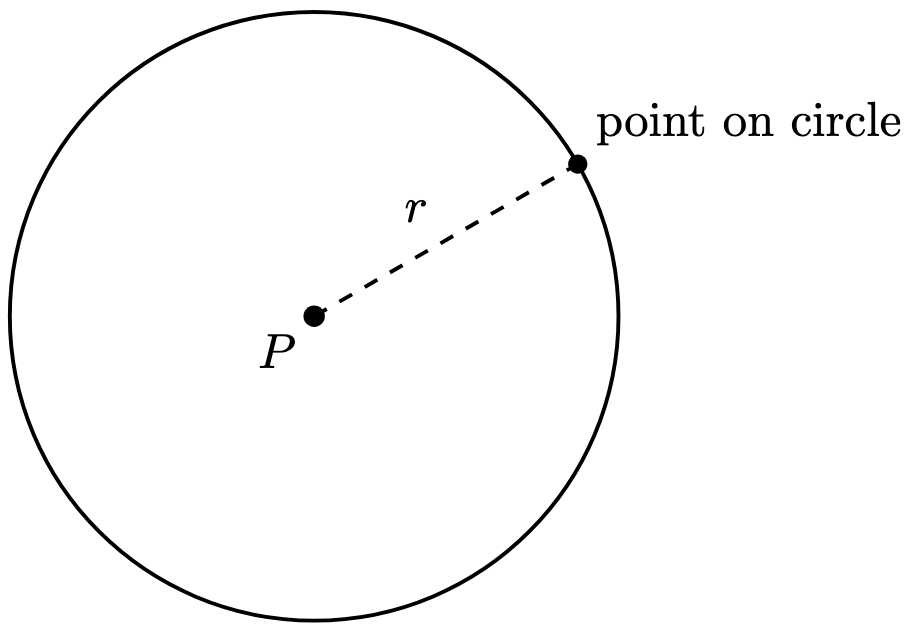

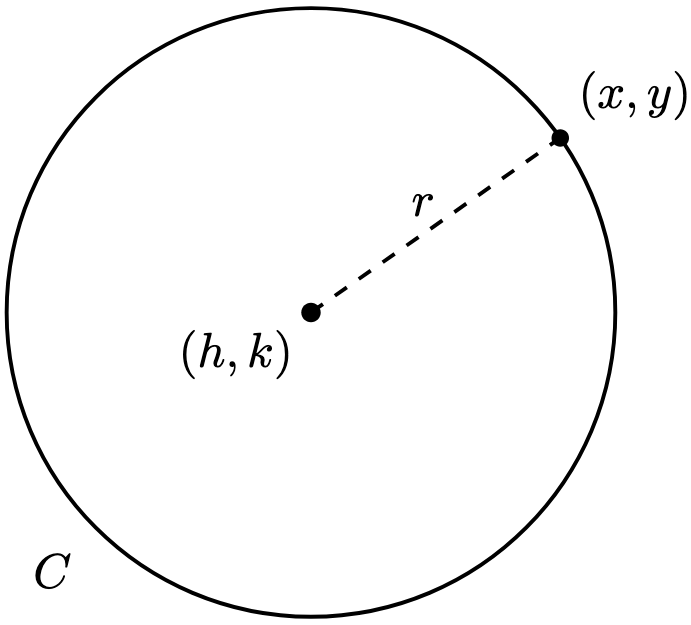

Definition 1. A circle with centre and radius

is the unique set of points whose distance from

is

. In particular, we define the unit circle to be a circle with centre

and radius

.

There is one problem with this definition: how do we calculate the distance between two points without requiring any additional measurement?

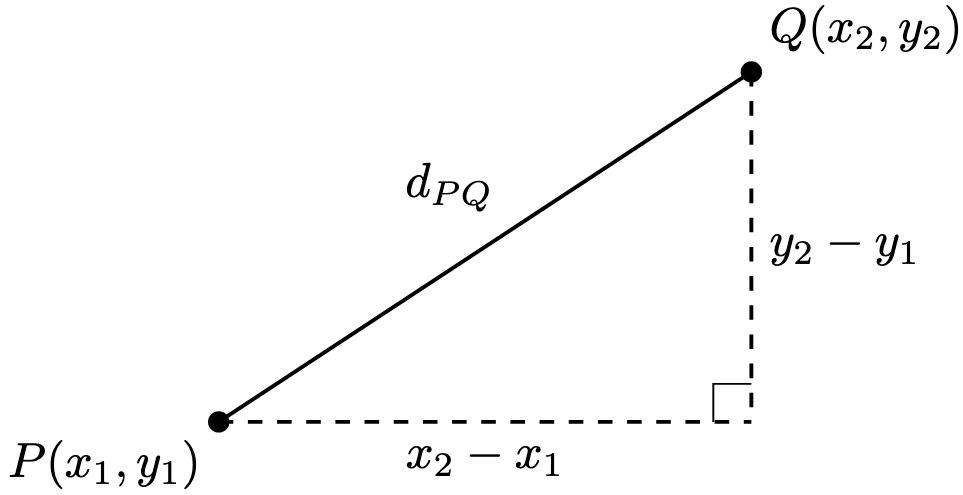

Lemma 1. The distance between two points

and

is given by

Proof Sketch. Suppose the special case and

.

Construct the right-angled triangle below.

Then the hypotenuse of this right-angled triangle has length . Applying Pythagoras’ theorem,

Taking square roots gives the desired result.

The other cases involving or

are left as an exerice to the reader.

Call any collection of points a graph.

Theorem 2. The graph is a circle with centre

and radius

if and only if it is defined by the equation

In particular, the unit circle has equation .

Proof. By definition, a point belongs to the circle if and only if its distance to

is

. By Lemma 1, this condition holds if and only if

Squaring on both sides, since , we obtain the equation

as required.

Once we can properly discuss circles, all sorts of interesting mathematics arise. But we will revisit circles later on.

For now, let’s answer the question we opened with: constructing geometrically.

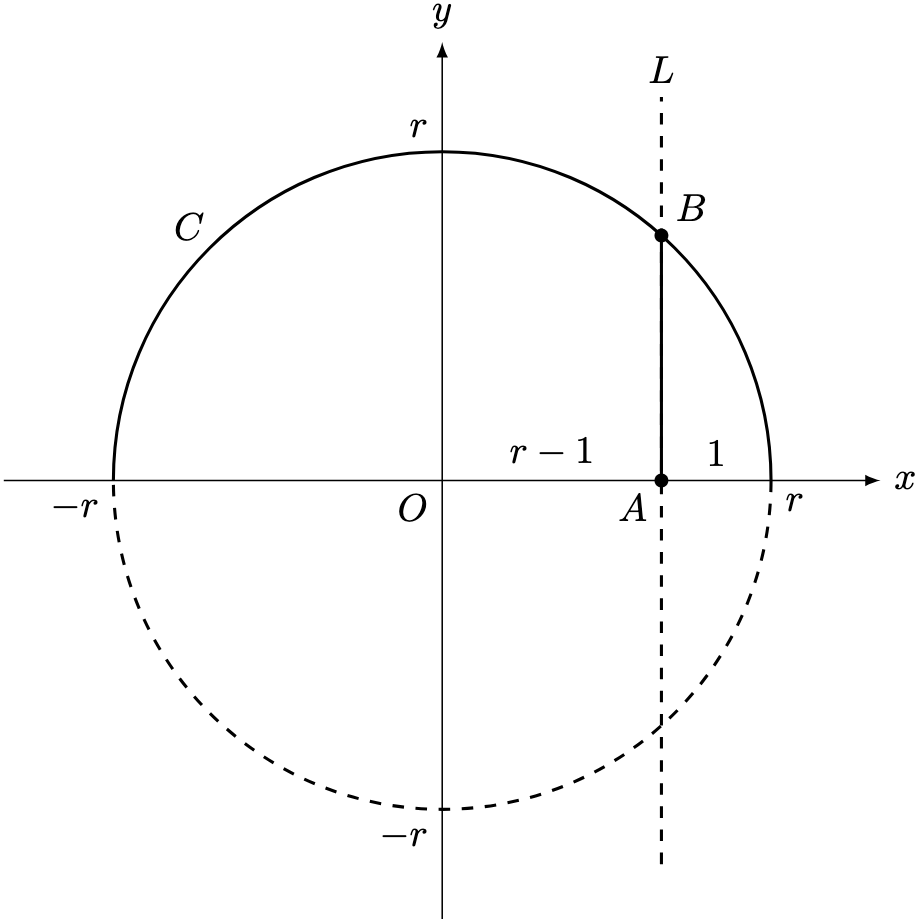

Theorem 3. Fix . Define

. Define the line

by

and the circle

to be a circle with centre

and radius

.

Then .

Proof. By Theorem 2, has equation

To obtain the coordinates of , we need to solve the equations

and require . We will use the substitution method as follows—substitute the equation

into the circle equation:

Since , by definition,

. Since

and

, by Lemma 1,

There is a lot more to circles than this one example, but for now, we return to triangles in the next post. In particular, the isosceles triangle will be a central tool in our geometric expedition.

—Joel Kindiak, 10 Oct 25, 2026H

Leave a comment