This is our motivating question for today:

What is the size of an angle in a triangle whose side lengths are equal to each other?

You might laugh at this question and reply: it is obviously

And your final answer is right—but how did you know that all three angles are equal to each other?

To answer this question properly, we need to properly discuss congruent triangles, from which we can discuss isosceles triangles, of which equilateral triangles are a special case.

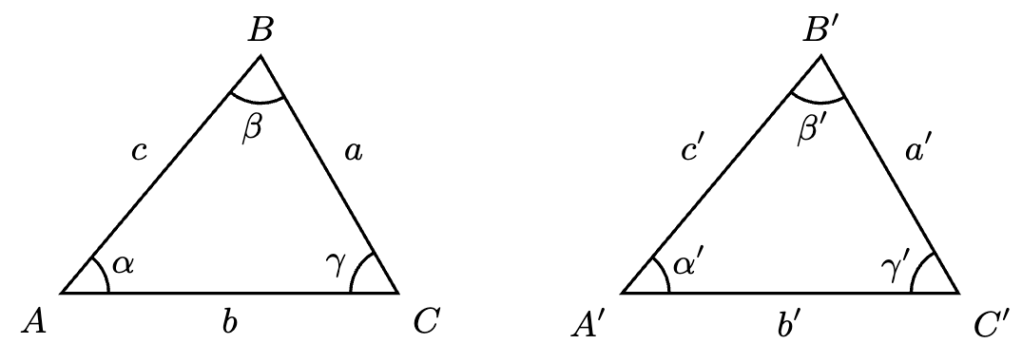

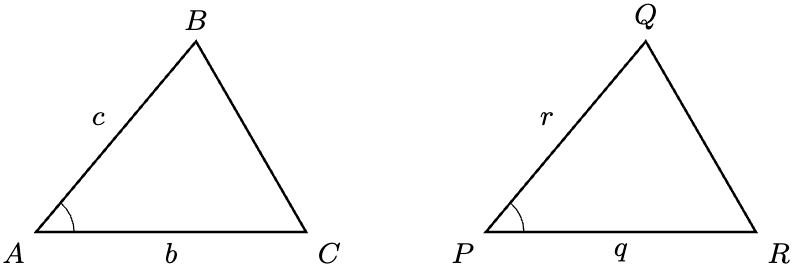

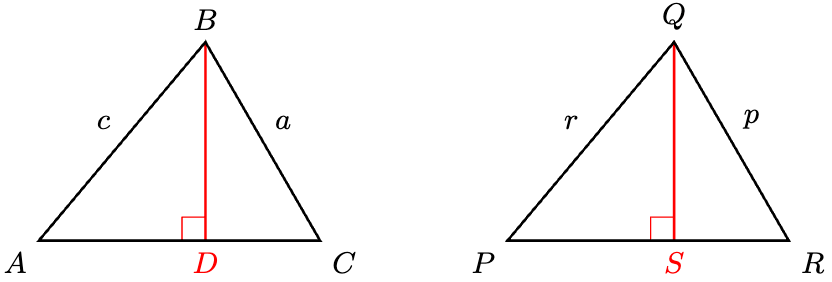

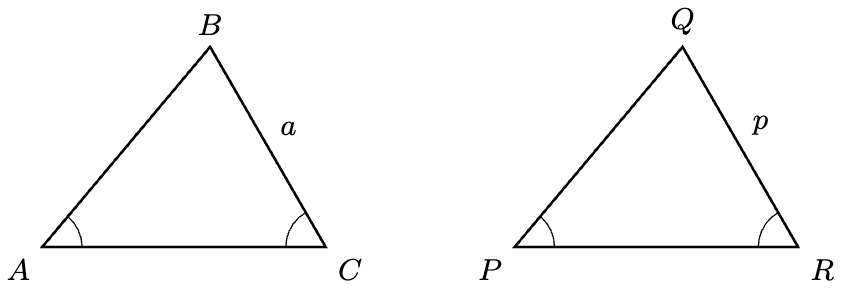

Definition 1. Consider the two triangles in the diagram below.

We say that is congruent to

, denoted

, if their corresponding side lengths and angles equal each other:

In ordered tuple notation:

The topic of congruent triangles is commonly presented as a collection of “cookbook recipes” to determine if two triangles are effectively the same.

But how do we know that these recipes actually work? It turns out that we have the necessary “meta-recipes” to construct these recipes, and that’s what we shall do.

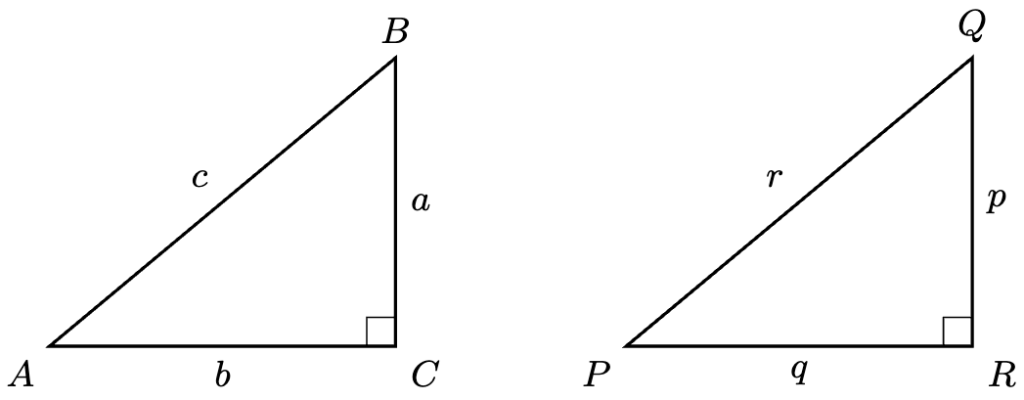

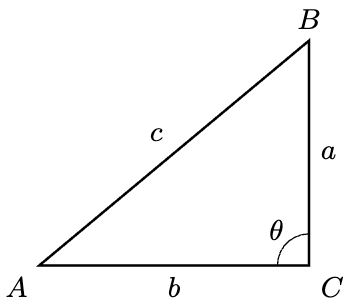

Theorem 1 (RHS Criterion). Let be the following two right-angled triangles with

:

Then if and only if

Proof. In the direction , we obtain all of the equalities by Definition 1.

For the direction , suppose

We will deal with the case later. Observe that exactly one of the following hold:

We claim that the remaining two cases are impossible.

Suppose . Then we can overlay the triangles on their edges

as follows:

Hence, so that

. However, by Pythagoras’ theorem,

a contradiction, ruling out the case .

The case can also be ruled out by relabelling

with

and vice versa, and using the same reasons above (i.e. a symmetric argument).

Therefore, .

Finally, since angles in a triangle sum to ,

Since all corresponding sides and angles equal each other, .

For the case , we could use a symmetric argument, or take the following even shorter approach: by Pythagoras’ theorem,

so that and

implies

, therefore

which, as shown just now, implies .

The RHS Criterion only describes congruence between right-angled triangles. Yet, more is true. Since right angles open our discussion on general angles, right-angled triangles also open our exploration of general triangles.

Theorem 2 (SAS Criterion). Let be the following two triangles:

Then if and only if

Proof. The direction is trivial.

For the direction , the hypothesis tells us that

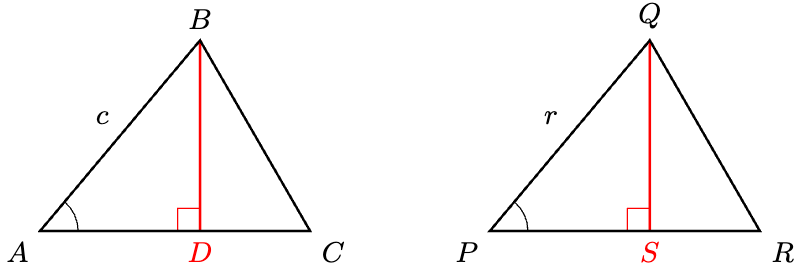

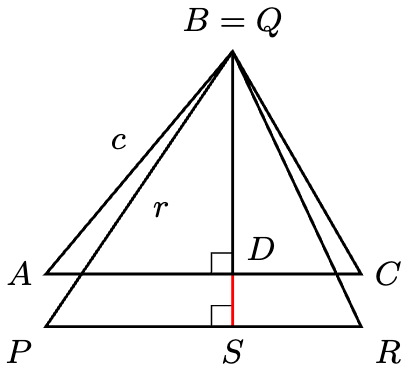

Construct the perpendicular heights (i.e. the altitudes) below.

Using rotation, we can assume . By construction,

are all right-angled triangles. Our line of attack is as follows:

- Show that

.

- Deduce that

using the RHS Criterion.

- Similarly,

.

- Conclude that

.

The first point is the most challenging.

Since and

and

, we must have

. We already have

by hypothesis, so it remains to prove

.

If , then aligning

with

, we can draw the diagram below.

By Pythagoras’ theorem,

Since and

, we have

, a contradiction. Similarly, we can rule out the case

. Therefore,

.

By the RHS Criterion, . In particular,

.

We next establish . By hypothesis,

. In particular,

By Pythagoras’ theorem,

Since and

, we have

. By the RHS Criterion again,

. In particular,

Finally,

Remark 1. This proof holds true in all three cases (i.e. and

can be acute, right, or obtuse), so long as both of the other two angles are acute.

Once we have a congruence criterion test that involves both sides and angles, we can derive many other useful congruence criterion tests.

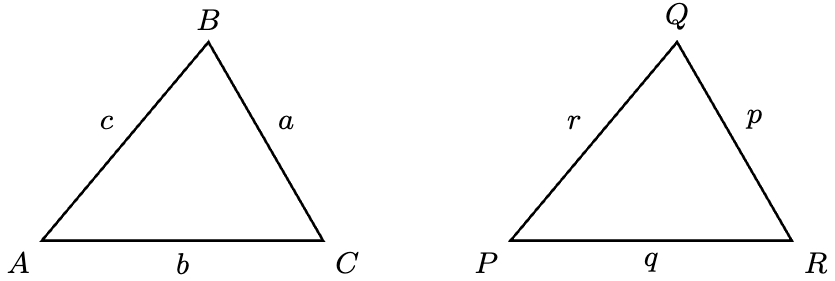

Theorem 3 (SSS Criterion). Let be the following two triangles:

Then if and only if

Proof. The direction is trivial.

For the direction ,

by hypothesis. Construct the altitudes once again.

If and

, then by Pythagoras’ theorem,

implies

so that , a contradiction. Therefore, by a symmetric argument, we can conclude that

.

By the RHS Criterion, , so that

By hypothesis, and

. Hence, by the SAS Criterion,

as required.

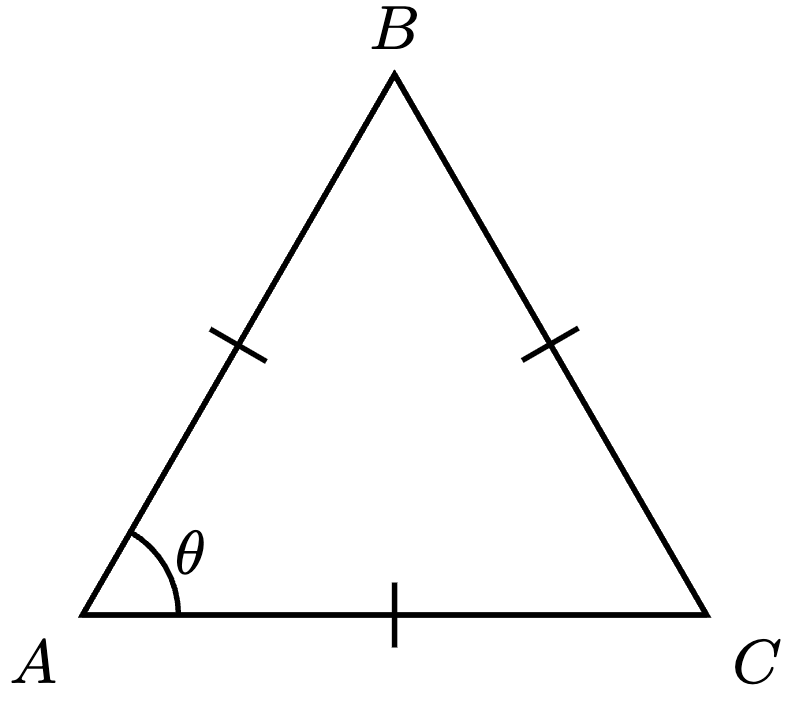

Example 1. Consider the triangle below.

Prove that if and only if

. The direction

is called the converse of Pythagoras’ theorem.

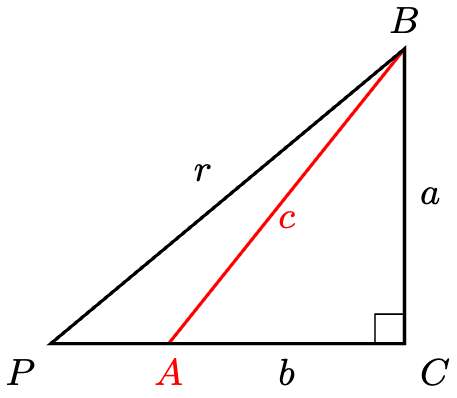

Solution. The direction is the already-proven vanilla Pythagoras’ theorem.

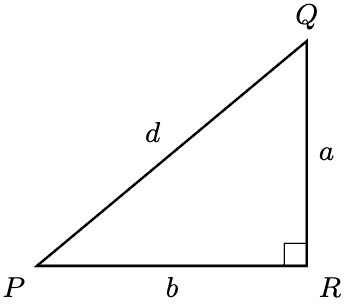

For the direction , suppose

. Construct a right-angled triangle

with base

and height

as follows:

By the vanilla Pythagoras’ theorem, . By hypothesis,

.

Since and

, we have

.

By the SSS Criterion, . In particular,

Theorem 4 (ASA Criterion). Let be the following two triangles:

Then if and only if

Proof. It suffices to prove . By hypothesis, since angles in a triangle sum to

,

Similar to the proof of Theorem 2, we claim that . Superimpose

onto

such that

and

.

Since the corresponding angles and

, we have

. Since

,

passes through

. By Playfair’s axiom,

must lie on

. Using a symmetric argument,

must lie on

.

Therefore, lies on the intersection between the line

and the line

. Since there exists one and only one intersection point between the two lines, namely

, we must have

, so that

.

By hypothesis, and

. Hence, by the SAS Criterion,

, as required.

Theorem 5 (AAS Criterion). Let be the following two triangles:

Then if and only if

Proof. Since angles sum to ,

Therefore, by the ASA Criterion, , as required.

Definition 2. A triangle is said to be isosceles if it has two sides with equal length.

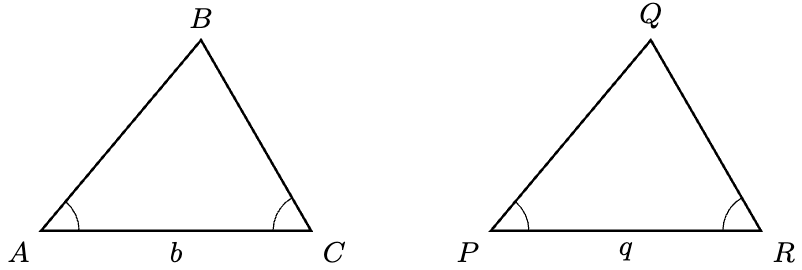

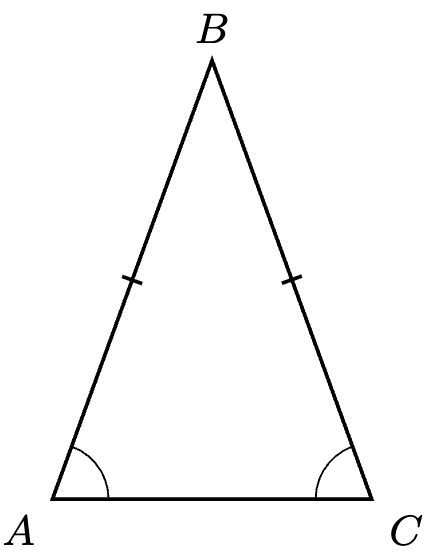

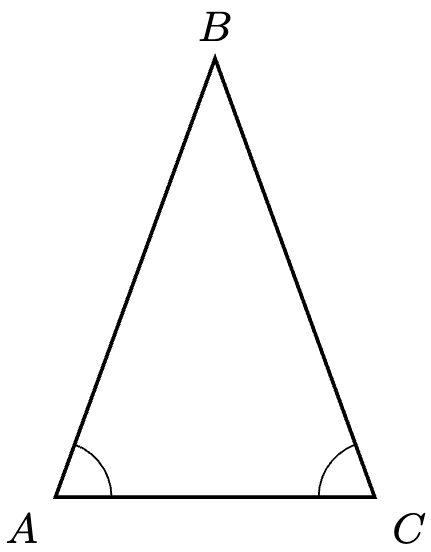

Example 2. Consider the triangle below with base angles

and

.

Prove that if and only if

. In this case, we say that the base angles of an isosceles triangle are equal.

Solution. Our proof boils down to the analysis of with its “rearranged” self

. Clearly

, since they denote the same angle.

We prove in two directions. For the direction , suppose

. Almost trivially,

and

. By the SAS Criterion,

. In particular,

.

The direction is proven similarly. Suppose

. Then by relabelling,

. Furthermore,

, since they denote the same side. By the ASA Criterion,

. In particular,

, as required.

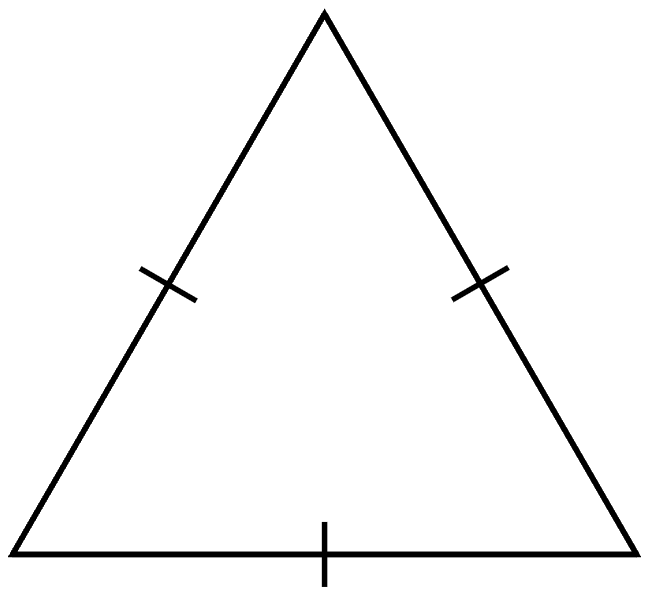

Definition 3. A triangle is said to be equilateral if all three sides have the same length.

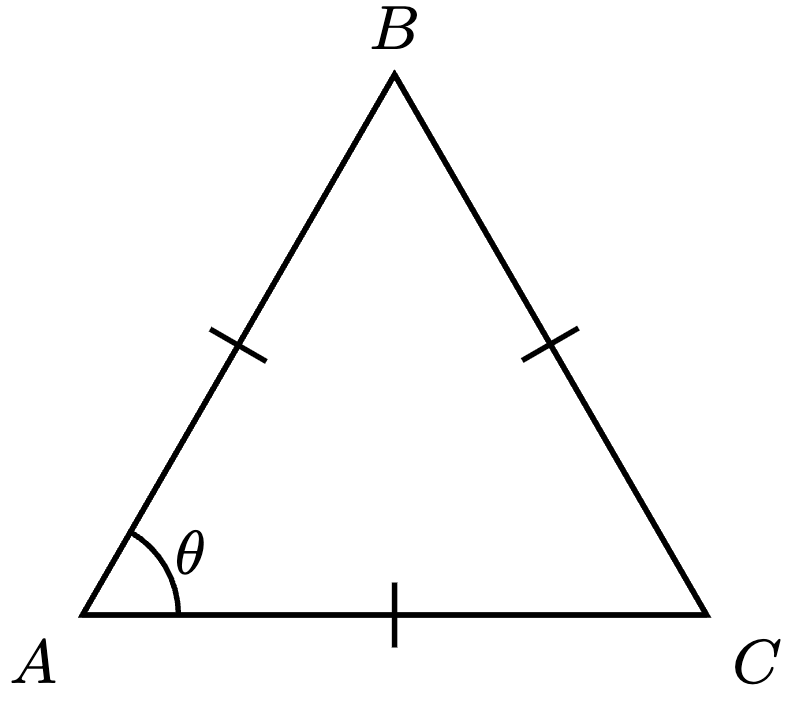

Example 3. Determine the size of any interior angle in an equilateral triangle.

Proof. Denote the equilateral triangle by , and denote

.

Since , by Example 2,

Since , by Example 2 again,

Since the angles in a triangle sum to ,

Therefore,

That is, each angle in an equilateral triangle has a size of .

If the geometry on a triangle is fascinating, the geometry on a circle is even more astounding! We will visit the geometry of circles in the next post.

—Joel Kindiak, 14 Oct 25, 1920H

Leave a comment