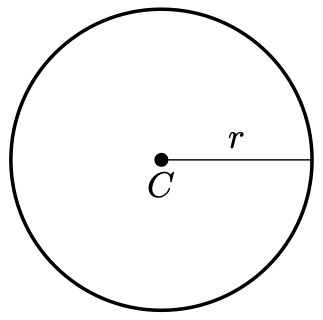

Recall that a circle with centre and radius

is simply the set of points whose distance from

is

.

This circular equidistant property is the vital source of many seemingly magical circle properties—and the isosceles triangle will help us greatly in this task.

Definition 1. For any two distinct points on a circle, we call

a chord, and the regions that it divides the circle into its segments.

The segment with smaller area is called the minor segment, and the segment with larger area is called the major segment.

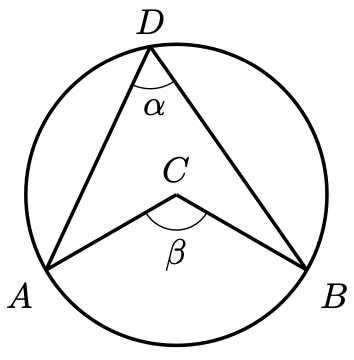

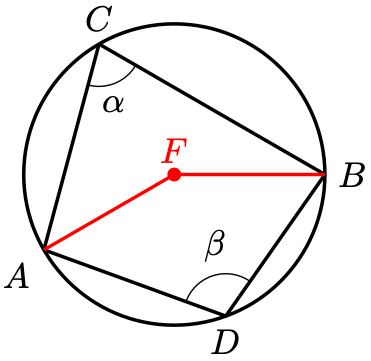

Theorem 1. Let be points on a circle with centre

. We call

the angle subtended by the chord

.

Then . That is, the angle at the centre of the circle equals two times the corresponding angle at its circumference. By “corresponding” we mean that

lie in the same segment.

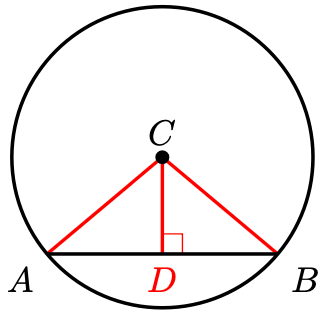

Proof. Connect as follows and extend

to the opposite end of the circle (i.e. turn it into a diameter).

Observe that as radii (plural for radius) of the same circle, . Hence, the triangles

and

are isosceles, and their respective base angles equal each other:

Since the external angle of the triangle equals the sum of the corresponding opposite interior angles,

Similarly, . Therefore,

Remark 1. If is obtuse, then the argument still holds and

. In this case, we say that

is reflex.

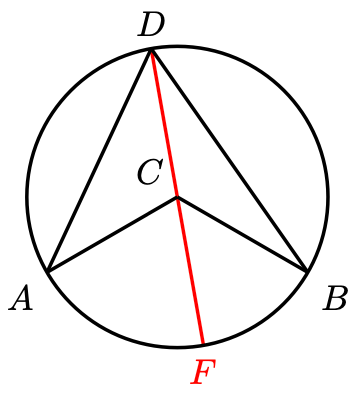

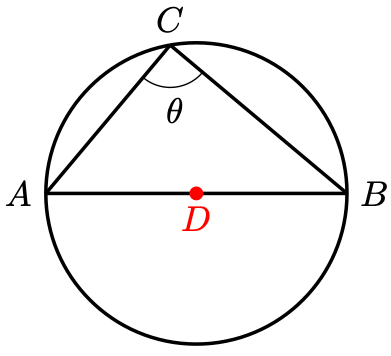

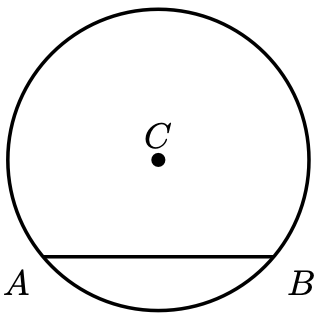

Corollary 1 (Thale’s Theorem). Consider the points on the circle below.

Then if and only if

is a diameter of the circle.

Proof. Denote the centre of the circle by .

By Theorem 1, . Hence,

which holds if and only if lies on

, and that holds if and only if

is a diameter.

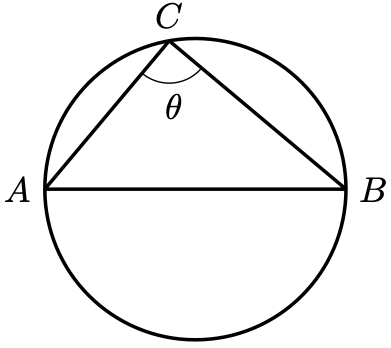

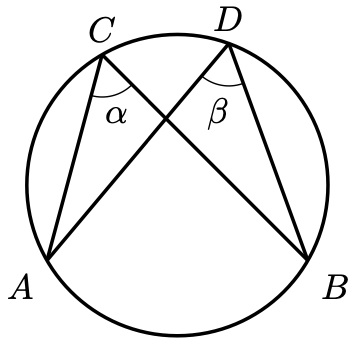

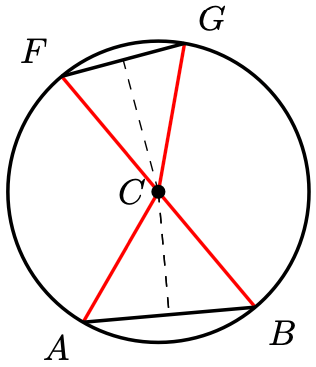

Corollary 2. Consider the points on the circle below.

Then . That is, angles subtended by the same chord equal each other.

Proof. Denote the centre of the circle by .

Applying Theorem 1 twice,

Therefore, .

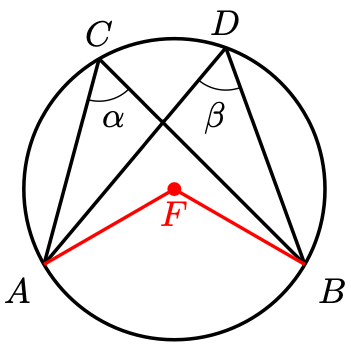

Corollary 3. Consider the points on the circle below.

Then . That is, angles in opposite segments sum to

(i.e. are supplementary).

Proof. Denote the centre of the circle by .

By Theorem 1, . By Theorem 1 again, the reflex angle of

equals

. Since angles at a point sum to

,

While we have derived many useful angle properties pertaining circles, the chords themselves are worth just as much attention, and their proofs aren’t even too difficult!

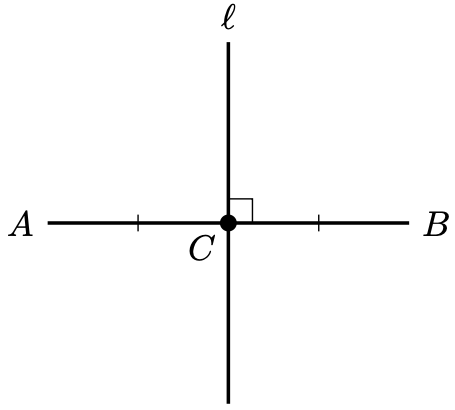

Definition 2. The midpoint of a line segment is the point

such that

.

Call the line the perpendicular bisector of

if

and it intersects

at the midpoint of

.

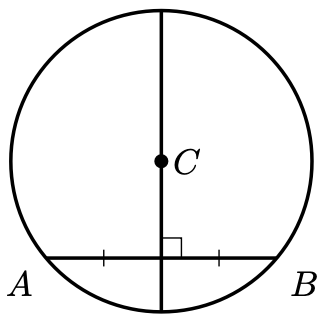

Theorem 2. Consider the points on the circle with centre

below.

Then the perpendicular bisector of will always intersect

.

Proof. Construct the edges and

for visibility and construct the altitude from

to

.

Since are radii of the same circle,

. Since adjacent angles on a straight line are supplmenetary,

. Since

is a common side, by the RHS Criterion,

.

In particular, , which means that

lies on the perpendicular bisector of

. Therefore,

lies on the perpendicular bisector of

, as required.

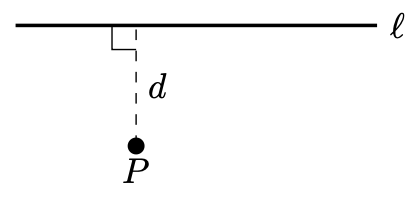

Definition 3. Define the distance from a point to a line

to be the shortest distance

between the point and any point on the line.

By Pythagoras’ theorem, this distance must be the length of the altitude from , perpendicular to

.

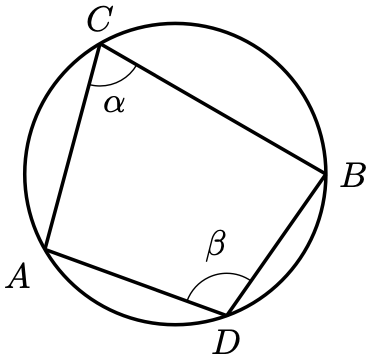

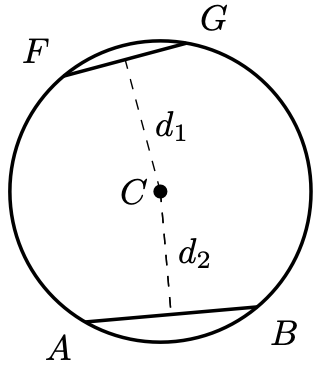

Theorem 3. Consider the points on the circle with centre

below.

Then if and only if

.

Proof. Construct the edges for visibility.

Since are radii of the same circle,

. By various triangle congruence criteria (left as an exercise),

There are several more properties needed to properly conclude our discussion on circles, but we will relegate them as exercises in proving techniques.

For now, we need to consider other kinds of shapes, such as four-sided shapes, known as quadrilaterals, as well as more general -sided shapes called polygons. We don’t need any new machinery—all that we have discussed so far is enough to establish these results, which we will explore next time.

—Joel Kindiak, 15 Oct 25, 2242H

Leave a comment