Many linear algebra texts open with a definition of the dot product, say in three dimensions, as follows:

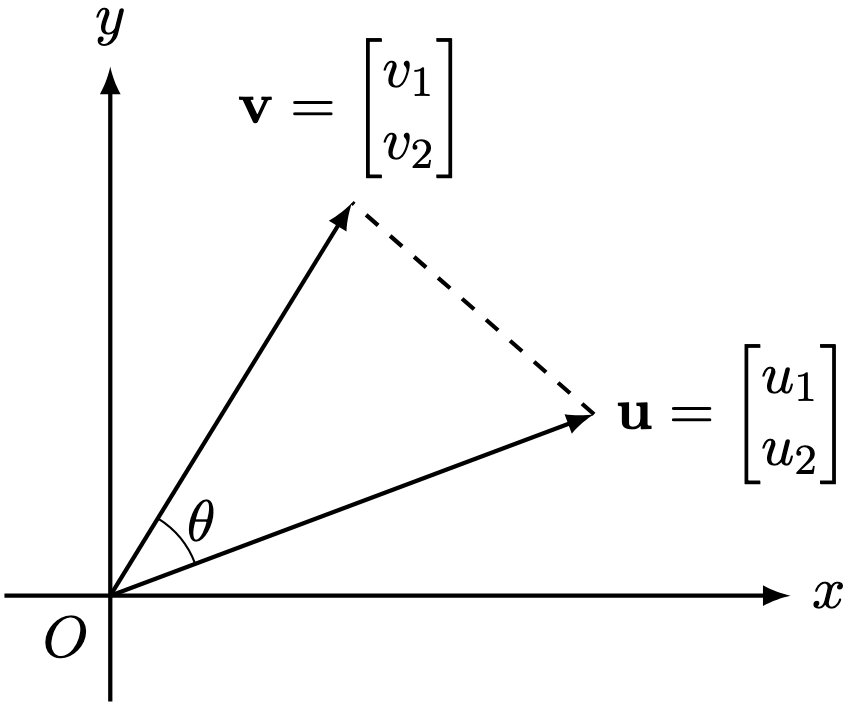

But where on earth did this formula arise from? Other authors open with a geometric definition with the dot product, but I shall open with a simple question: Given two vectors in the two-dimensional space, what is the angle

between

and

?

Motivated by the Pythagorean theorem, we can define the length of a two-dimensional vector as follows.

Definition 1. Given , the norm of

is defined by

Intuitively, this quantity captures the length of .

Consider two vectors .

Consider the triangle where

,

,

:

so that

Using the law of cosines,

Equating the two displays for then doing algebruh,

Therefore, the angle between can be computed using the sum-product

, which we abbreviate by the dot product notation

so that we obtain the dot product equation

Yet, the dot product is itself of considerable interest. We can generalise it and talk about angles between other kinds of objects using this idea. This generalisation also features heavily in scientific applications like regression analysis. We can even use the dot product to give a theoretically useful meaning to the transpose of a matrix. More on these ideas in future posts.

Theorem 1. For any two vectors in two-dimensional space, define their dot product by

.

The dot product satisfies the following properties:

- For any

,

.

- For any

,

implies

.

- For any

,

.

- For any

, defining

by

, the functions

and

are linear over

.

Furthermore, for nonzero ,

Proof. The second property is slightly tricky. Fix . Then

Hence, . Similarly,

. Therefore,

.

The dot product motivates the defining properties of the inner product, which we formulate to generalise the dot product.

Let be either

or

.

Definition 1. A map is said to be an inner product on

if it satisfies the following properties:

- For any

,

.

- For any

,

implies

.

- For any

,

. When

, we recover usual symmetry.

- For any

, the map

is linear.

The pair is called a

–inner product space.

Corollary 1. The dot product of two-dimensional vectors (i.e. in ) as defined in Theorem 1 forms an inner product space.

Henceforth, suppose is an inner product on

.

Lemma 1. For any , define the quadrance of

by

The following properties hold:

- For any

,

.

- For any

,

implies

.

- For any

,

,

.

Proof. For the third property, we have

Lemma 2 (Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality). For any ,

Proof. Fix . If either

or

are

, define

. Otherwise, define

In either instance, we have and

.

Define the function by

By expanding the definition of , we obtain

Since for any

, we must have

yielding .

Theorem 2. For any , define the norm of

by

. The following properties hold:

- For any

,

.

- For any

,

implies

.

- For any

,

,

.

- For any

,

.

We call a normed space.

Proof. For the last result, we use the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality to derive that

where we defined for

, and observe that for any

,

.

Corollary 2. For any nonzero , define the unit vector

of

by

Then . In particular, if

, for nonzero

, define the angle between them

by

Then .

Proof. For the final result, we note that . Then

Corollary 3. Define the metric by the map

The following properties hold:

- For any

,

.

- For any

,

implies

.

- For any

,

.

- For any

,

.

We call a metric space.

Proof. For the last result, use the observation

Therefore, all inner product spaces are normed spaces, and all normed spaces are metric spaces. By some further investigation, every metric space forms a topological space too. If we took a different generalisation from the usual narrative, we would have explored the notion that all normed spaces are topological vector spaces, which in turn are topological spaces.

Each generalisation has their uses in modern mathematics, but for now, let’s focus on inner product spaces. We will first explore the theory of inner product spaces before exploring their ubiquitous applications across mathematics.

—Joel Kindiak, 12 Mar 25, 1407H

Leave a comment