Calculus, in the 21st century, continues to be the sorrow of most students required to learn it against their will. It doesn’t need to be this way, though.

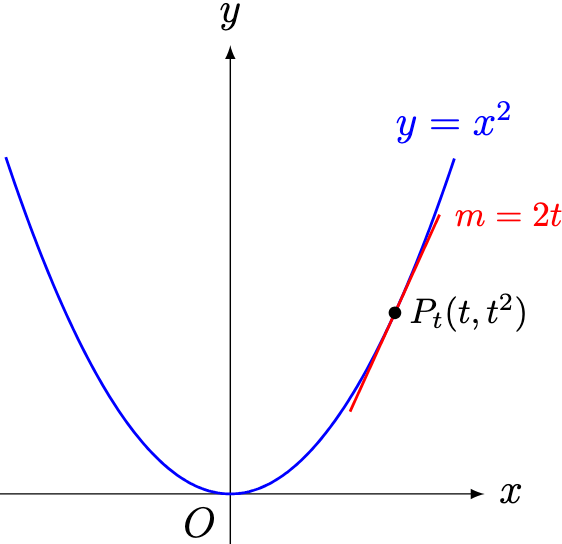

Consider the graph of below.

Define the point on the graph by

. Using algebra, we can evaluate the gradient of the tangent at

to

.

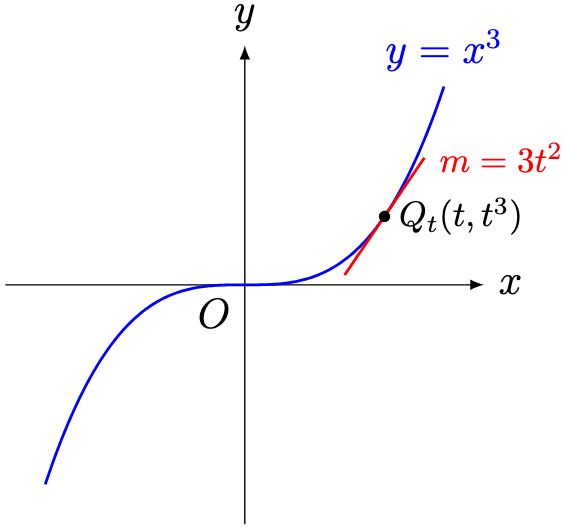

Now consider the graph of .

Define the point on the graph by

. Using algebra, we can evaluate the gradient of the tangent at

to

.

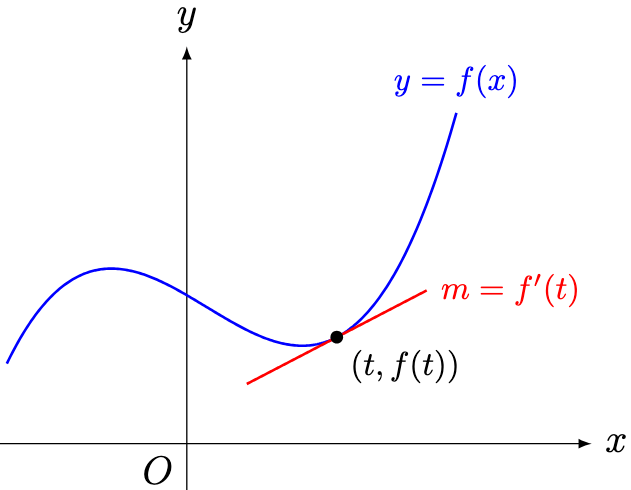

We are going to generalise this observation.

Definition 1. Let be the graph of a function. The derivative of

at

, denoted

, is defined to be the gradient of the tangent at

.

Define the derivative of by

Since , we can also write

We describe this process as differentiating with respect to

.

Remark 1. Strictly speaking, the derivative is defined as a limit, and the gradient of the tangent is defined to be the derivative. However, we adopt the convention in Definition 1 for the sake of visual intuition.

Using more mathematical tools to establish a common pattern, we will define the derivative of , where

is any rational number.

Theorem 1. The derivative of with respect to

is given by

Proof. See this post for the more formal perspective, and see this exercise for the algebraic calculation. We see that

and these results agree with our investigation in earlier examples.

Example 3. Evaluate the following derivatives:

Solution. The first expression is immediate using Theorem 1:

The second expression requires the two laws of exponents and

:

The third expression requires :

The fourth expression requires and more generally,

:

The fifth expression requires and

:

Is it possible to evaluate derivatives of combinations of these functions? Yes!

Theorem 2. Given functions and constants

,

Proof. See this post from a calculus perspective and this post from a linear-algebra perspective. This result is known as the linearity of the derivative.

Example 4. Given functions , show that

Solution. Using the linearity of the derivative,

Example 5. Evaluate the following derivatives:

Solution. For the first expression, we use linearity as per Example 4:

Using the results in Theorem 1 and Example 3, we have

For the second expression, we expand , then use the previous answer:

For the third expression, we first expand :

We then use linearity and established results as per Theorem 1 and Example 3:

To shorten notation, we write .

Example 6. Given functions , show that

Solution. Since , we use linearity to derive

Example 7. Let be positive constants. In economics, the revenue

earned from selling

units of a good is given by

Define the two quantities related to the revenue:

- The average revenue is defined by

.

- The marginal revenue is defined by

.

Show that the -intercept of

is half of the

-intercept of

.

Solution. By algebra, and

Using linearity,

Let denote the

-intercept of

and

denote the

-intercept of

.

We first solve :

We next solve :

Hence, , so that

.

What other combinations can we differentiate? Given functions , we can differentiate the following:

Tragically, they don’t follow the neat rules that we think they do.

Example 8. Which of the following equations are true?

Justify your answer.

Solution. Sadly, none of them are true.

We will use the counter-example and

. Using Theorem 1,

and

.

For the first equation,

however,

Therefore,

For the second result, we leave it as an exercise to check that

For the third result, we leave it as an exercise to check that

To deal with these latter three results, we will need to look at the three musketeers of differentiation techniques: the chain rule, the product rule, and the quotient rule. For more complete proofs, see this post on the chain rule and this post for the product and quotient rules.

We will explore this differentiation trio next time.

—Joel Kindiak, 7 Jan 26, 1450H

Leave a comment