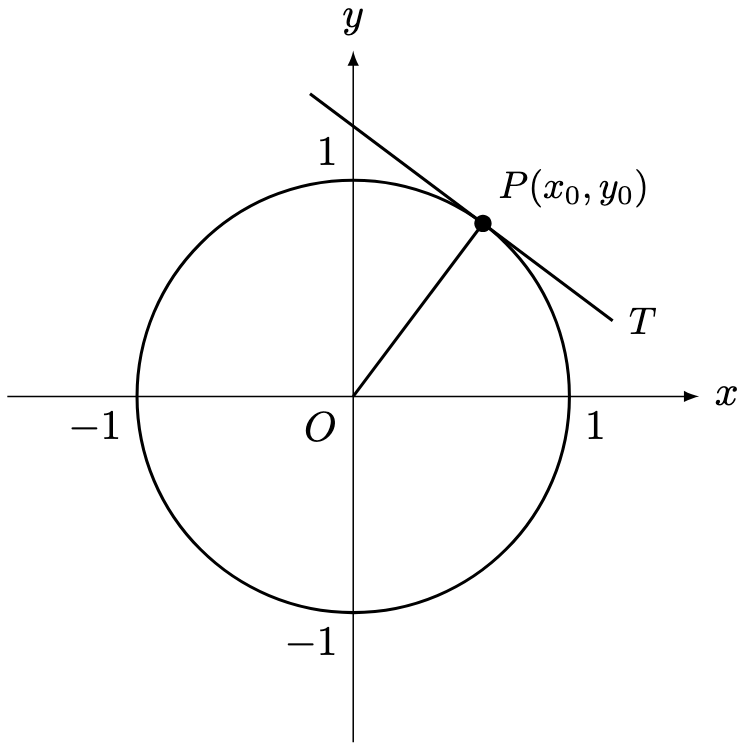

Problem 1. Consider the circle below with equation .

Given and

, calculate the gradient of the tangent

passing through the point

lying on the circle. Deduce that

.

(Click for Solution)

Solution. Since lies on the circle,

For any line with gradient passing through

,

When the line intersects the circle,

Expanding the left-hand side, since ,

Hence, or

For to be a tangent with gradient

, we require

to be the only root. Hence, we must have

Solving for ,

On the other hand, , so that

Therefore, . We recover the tangent is perpendicular to radius property of circles.

Remark 1. The same argument holds for any general circle, with more careful book-keeping.

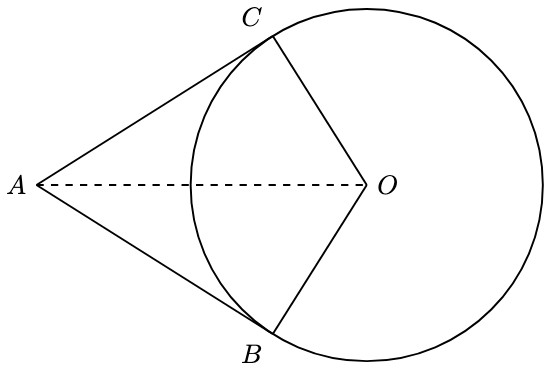

Problem 2. Given that and

are tangents to the circle, show that

and

bisects

.

This result is described by the phrase tangent from external point.

(Click for Solution)

Solution. By Problem 1, and

. As radii,

. As a common side,

. Therefore, by the RHS Criterion,

In particular, and

. Hence,

bisects

.

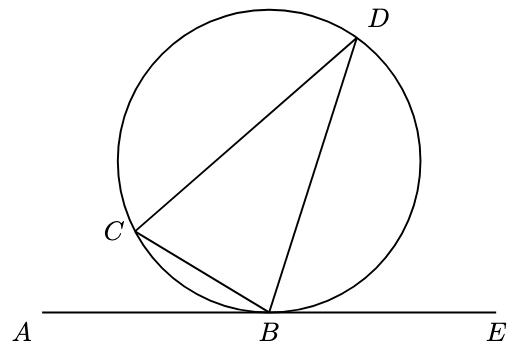

Problem 3. Given that is tangent to the circle, show that

. Deduce that

. This result is known as the alternate segment theorem.

(Click for Solution)

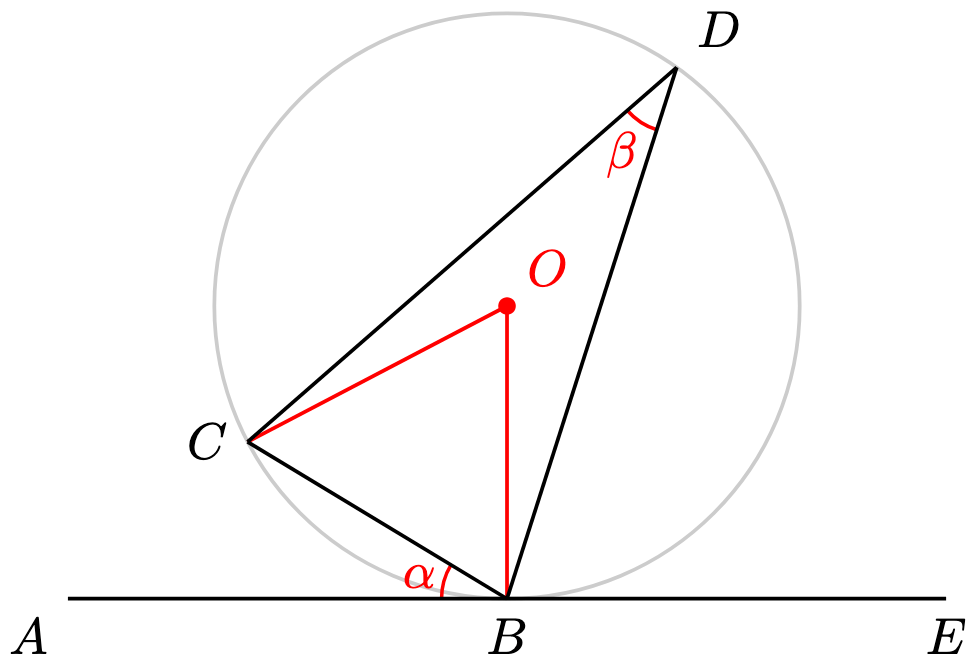

Solution. Make the following constructions, with denoting the centre of the circle.

We aim to prove that . By Problem 1,

. Hence,

Since as radii,

is isosceles. Hence,

Since the angle at the centre equals twice the angle at the circumference,

Since angles in a triangle sum to ,

Substituting the displays,

Therefore, , as required.

For the second result,

—Joel Kindiak, 9 Jan 26, 1146H

Leave a comment