The three-dimensional version of “area” and “perimeter” would be, rather unsurprisingly, “volume” and “surface area”.

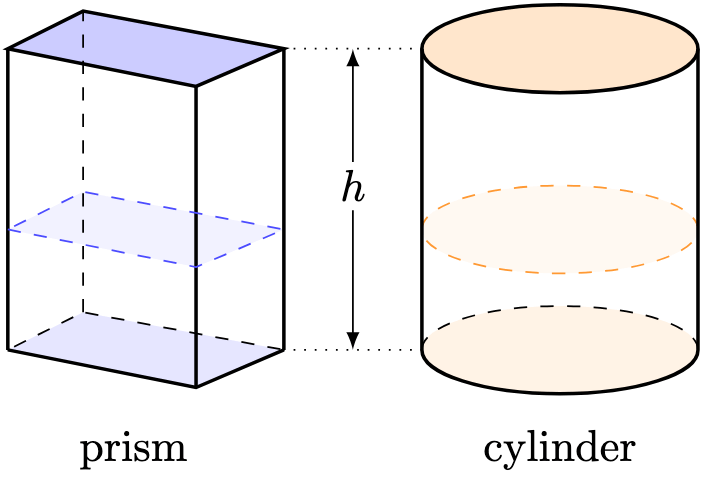

We start with the simplest object: a prism.

Definition 1. A solid with height is called a prism if all of its cross-sections have the same shape. In the special case that the base of the prism is a circle, we call the solid a cylinder.

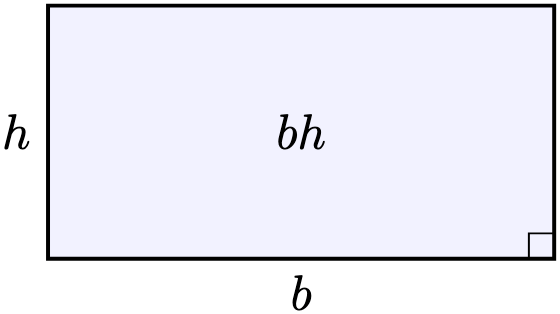

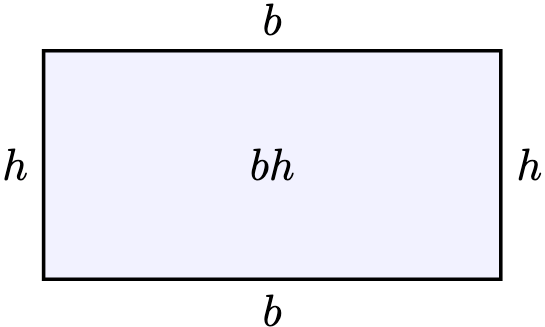

Just like how a rectangle has area , a prism also has volume

In that sense, a prism is similar to a “three-dimensional” rectangle, with many possible shapes for its base.

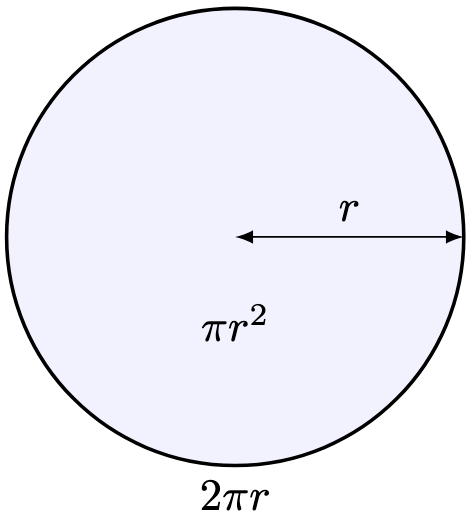

Corollary 1. The volume of a cylinder with height and base radius

is

.

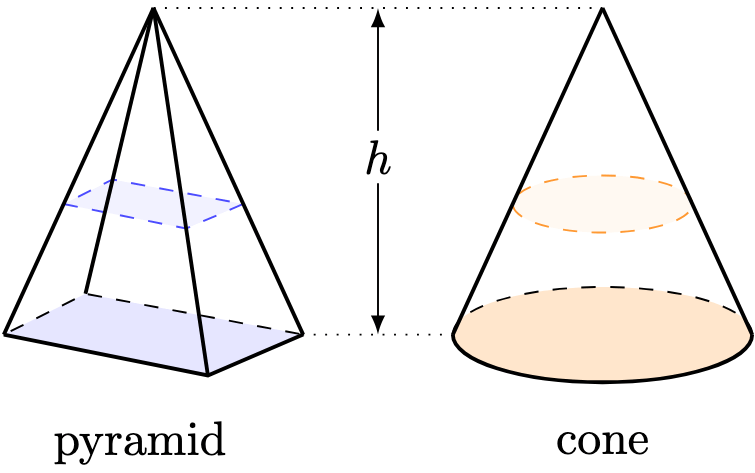

If there’s a “three-dimensional” rectangle, is there a “three-dimensional” triangle? Yes, and it’s called a pyramid.

Definition 2. A solid with height is called a pyramid if all of its cross-sections are similar to one another, and they “shrink” to a common point. In the special case that the base of the prism is a circle, we call the solid a cone.

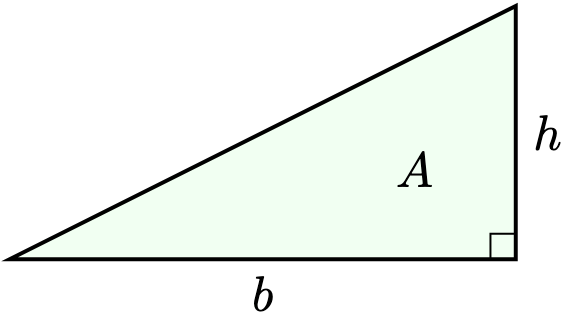

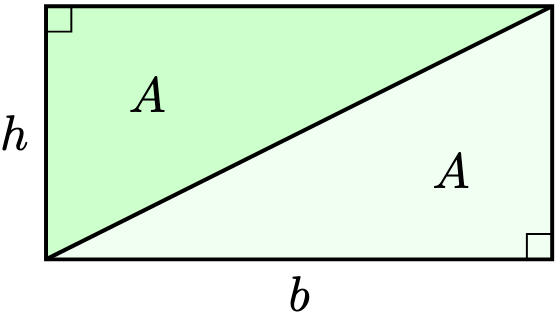

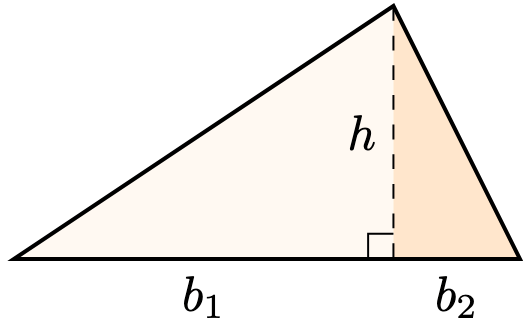

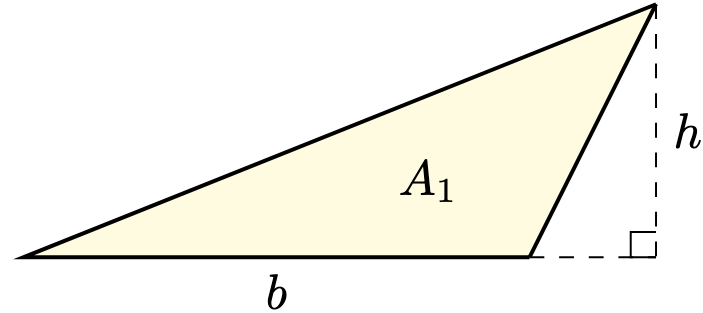

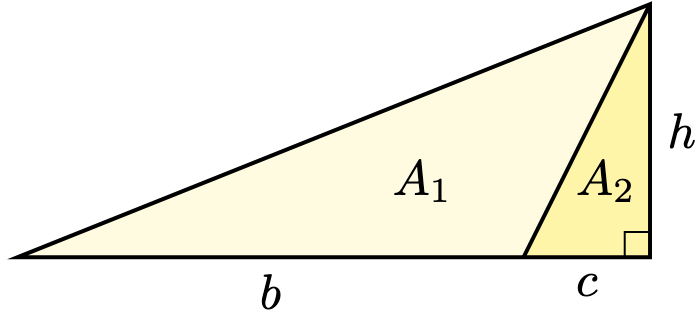

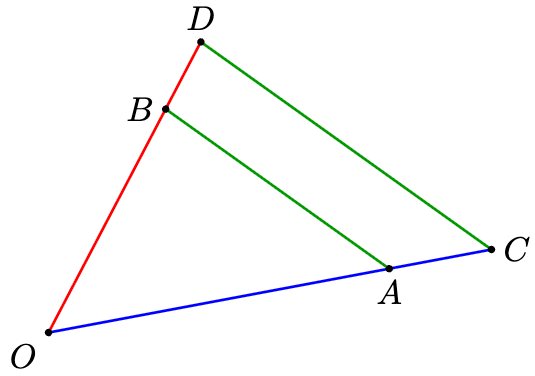

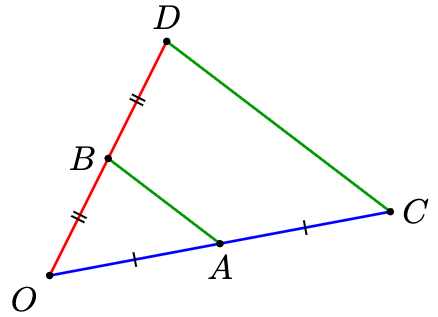

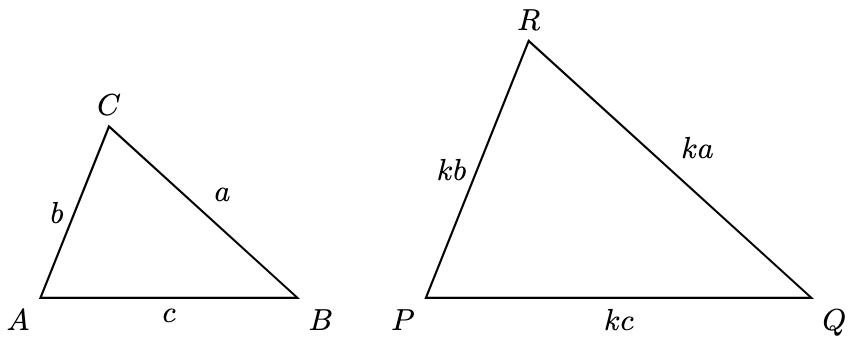

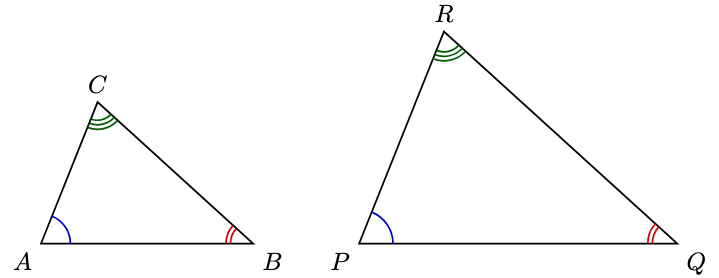

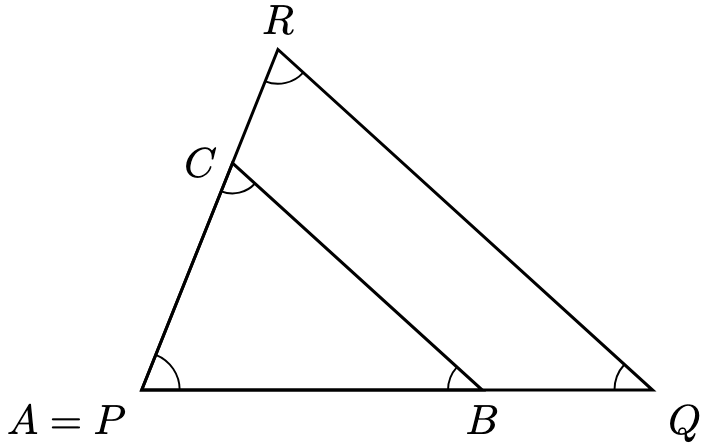

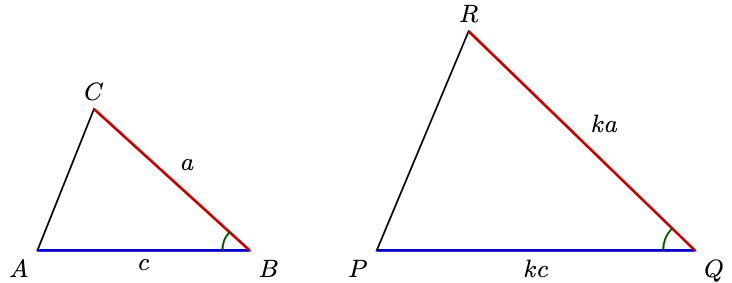

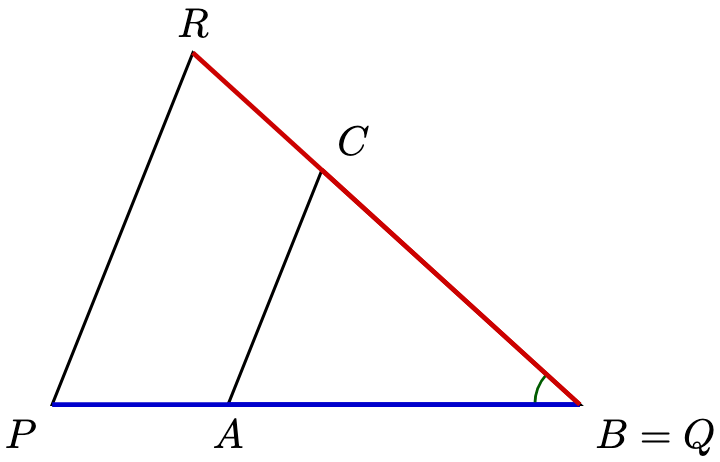

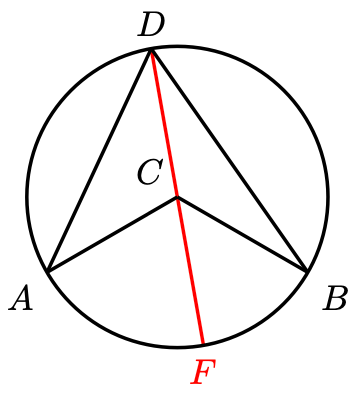

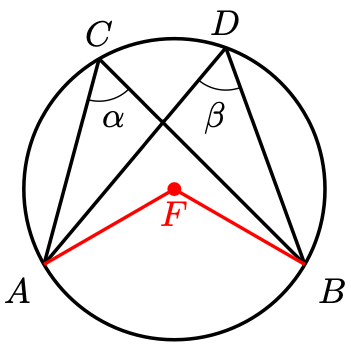

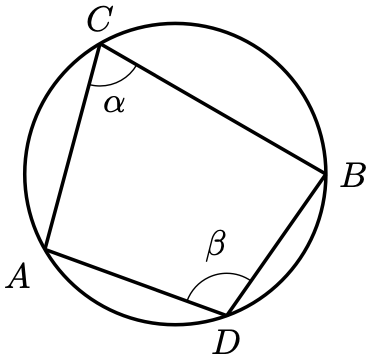

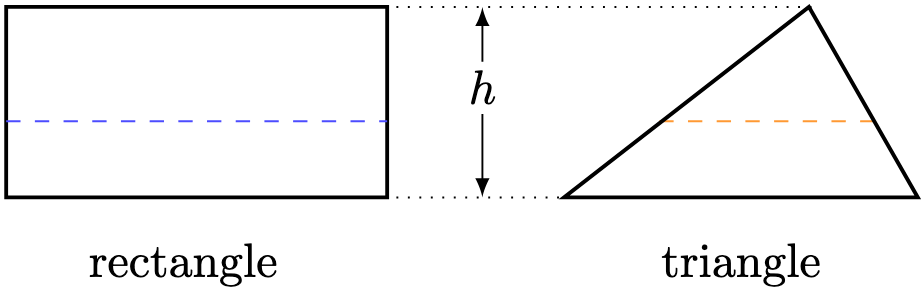

This description is similar to that of a triangle: the bases are similar to one another and “shrink” to a common point:

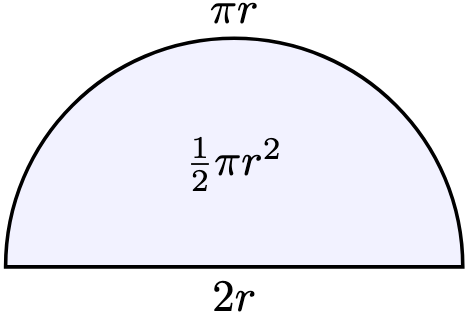

We have seen that a triangle has area . What’s the formula for that of a pyramid?

Theorem 1. The volume of a prism is .

Proof. Omitted as it requires integral calculus. Nevertheless, the factor is directly related to the

dimensions in which we defined a pyramid.

Corollary 2. The volume of a cone with height and base radius

is

.

Proof. By Theorem 1, the cone has a volume of

Having discussed volumes, it’s worth looking into its partner, surface areas. As the name suggests, surface areas refer to the areas of the surfaces of a solid. But what happens when weird faces abound?

We can’t discuss them all, but there are some special cases.

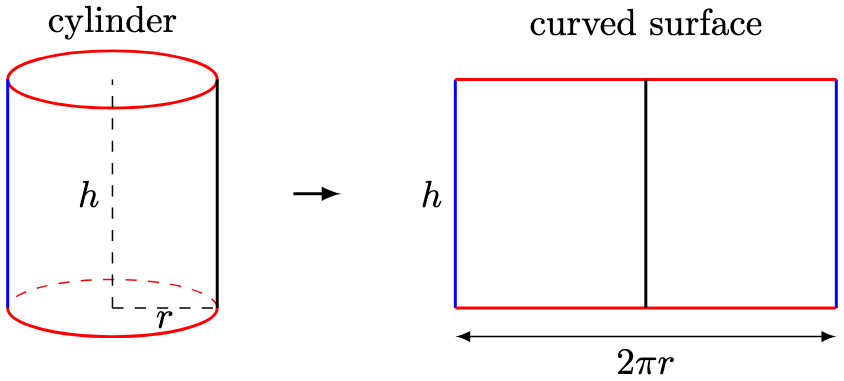

Theorem 3. The curved surface area of a cylinder with height and radius

is

.

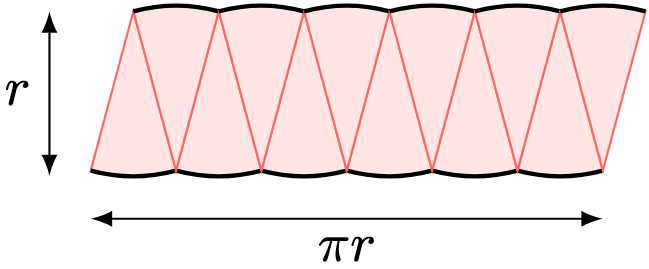

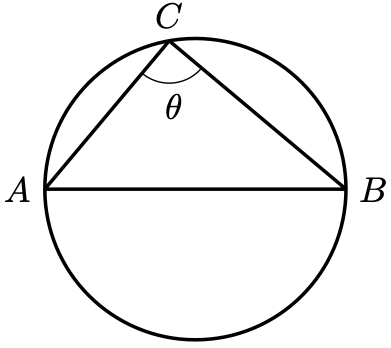

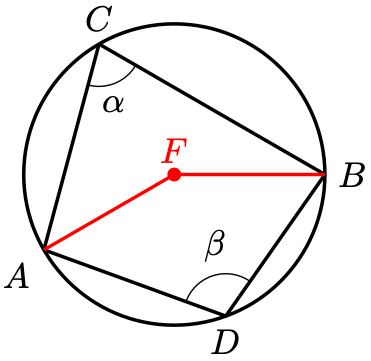

Proof. The curved surface area of a cylinder can be thought of as a “wrap” of a rectangle with base and height

:

Hence, the curved surface area is .

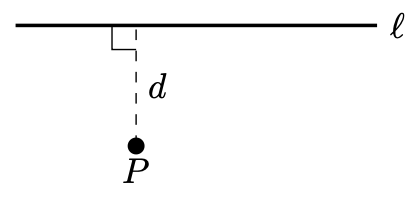

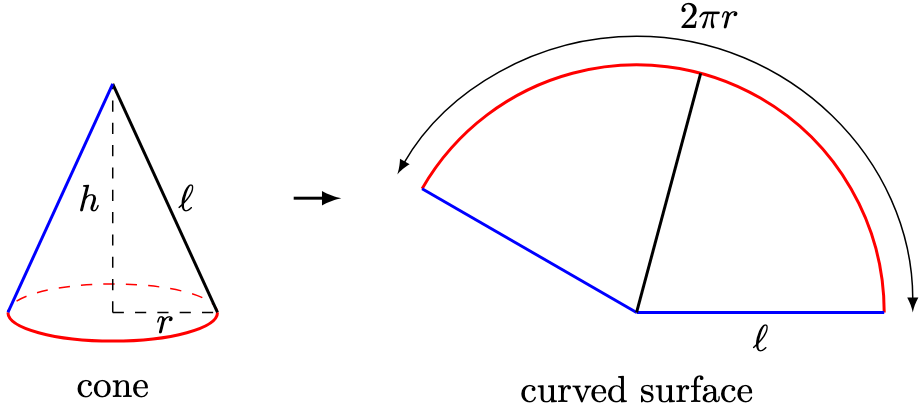

Theorem 4. The curved surface area of a cone with height and radius

is

.

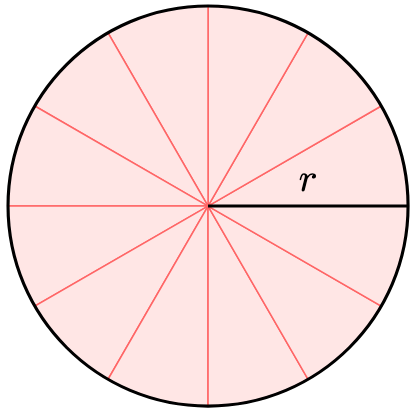

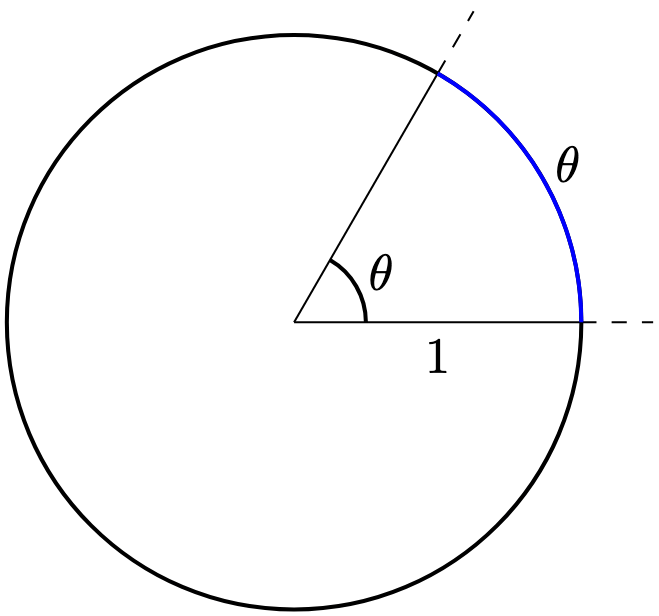

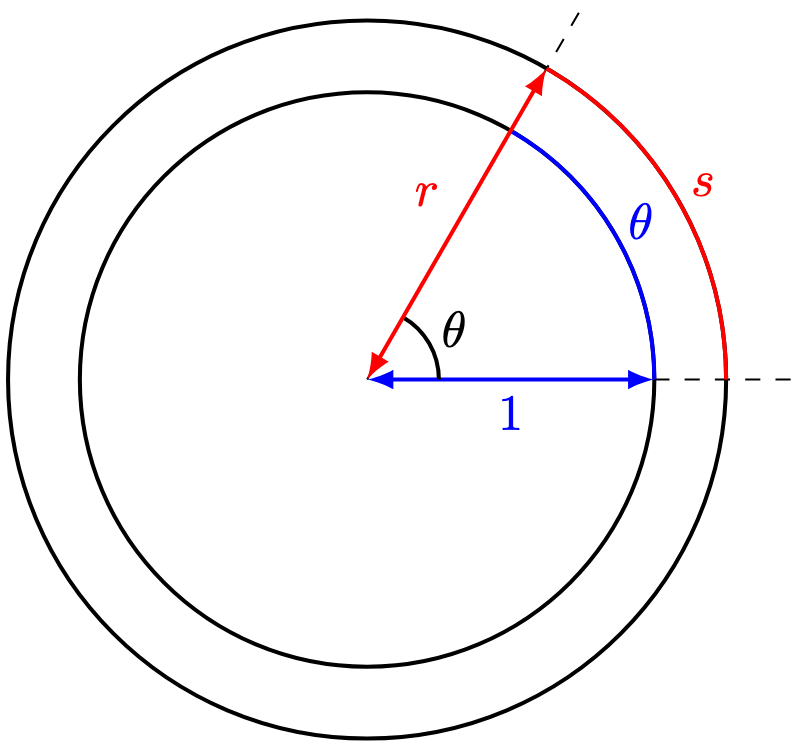

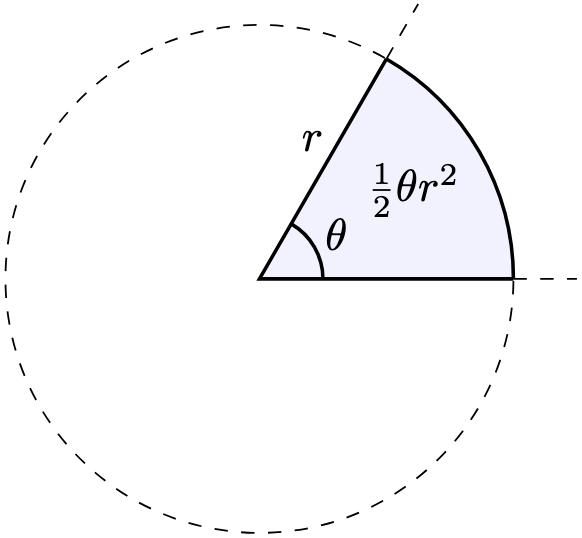

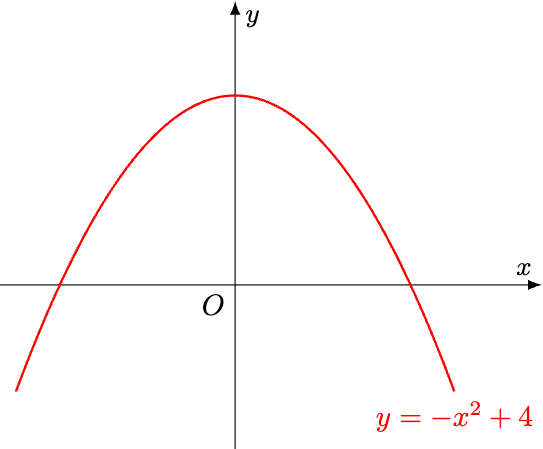

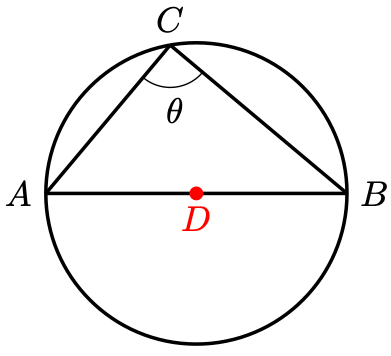

Proof. Let denote the slant height of the cone. The curved surface area of a cone can be thought of as a “wrap” of a sector with radius

:

Now the length of the arc of the sector is the circumference of the original cone, namely, . Hence, the total area of the sector is given by

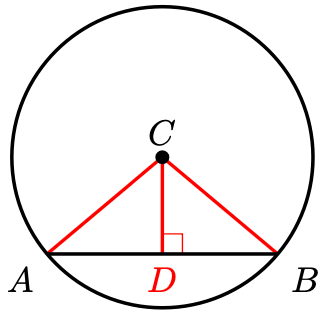

Now by Pythagoras’ theorem,

Therefore, the curved surface area is , as required.

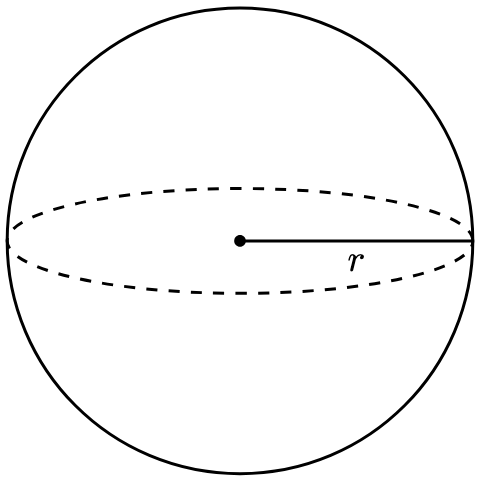

Finally we should discuss the geometry of the three-dimensional version of a circle: the sphere.

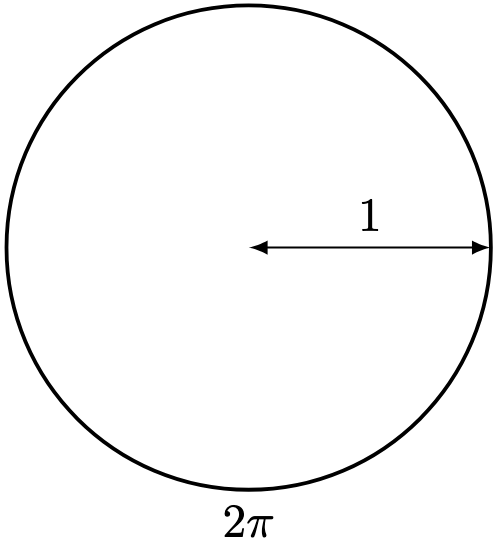

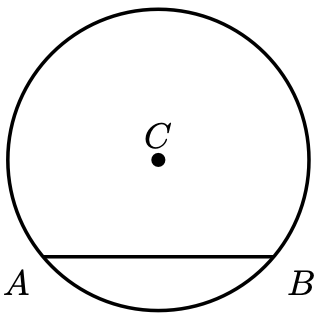

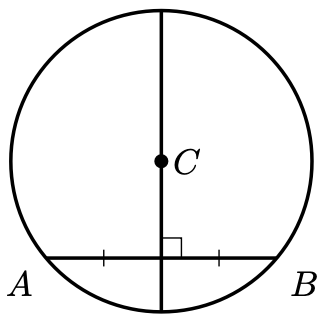

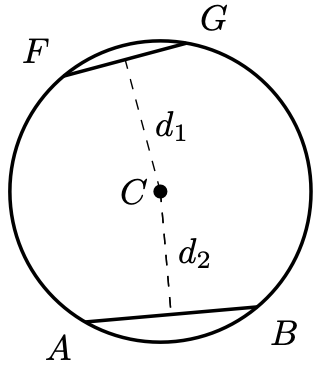

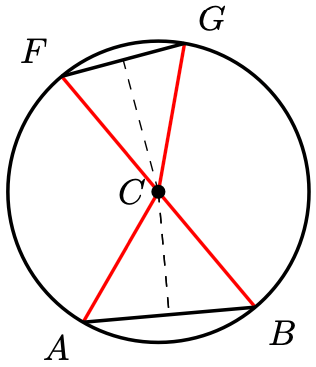

Definition 2. Define the sphere with centre and radius to be the set of points whose distance from the centre is

.

Example 1. The Earth can be modelled as a sphere.

Source: Wikipedia

Theorem 5. The volume of a sphere with radius is

. The surface area of a sphere is

.

Proof. Omitted as it requires integral (and arguably, differential) calculus.

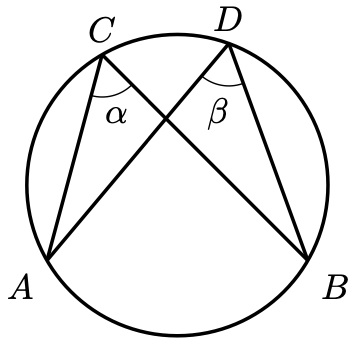

Having developed the many commonly-used formulas in high school geometry, we cannot avoid the dreaded T-word: trigonometry. Contrary to popular anxiety, trigonometry is simply a new language to describe the relationship between straightedges and curves (i.e. angles). More on that in the next post.

—Joel Kindiak, 7 Dec 25, 1931H