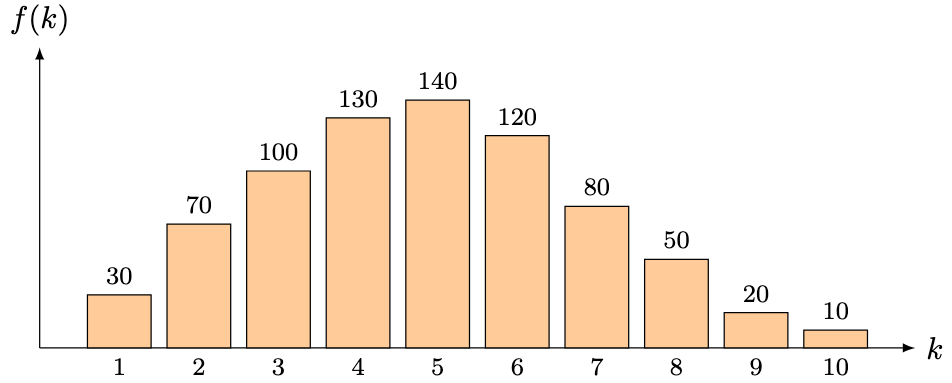

In this appendix for the multi-armed bandit writeups, I thought I’d revisit my final year project in a relatively readable manner, demonstrating how -Thomoson Sampling is asymptotically optimal for Bernoulli bandits (that is,

for each

). This is the instantiation

of my final year project.

As a set-up, we initialise with p.d.f.

since the conjugate prior of a Bernoulli distribution is the Beta distribution. For the update function, we use

and . At each time

, we sample

and pull the arm

Observe that the map induces a unique map

given by

. Following the Thompson sampling strategy, we need to obtain useful tail concentration bounds. We will impose some technical conditions on the risk functional

to make this happen.

Definition 1. Call a risk functional continuous if

is continuous.

If is continuous, then by the extreme value theorem,

is compact. Hence, there exists

such that for any

,

Lemma 1. If is continuous, then for any

and

, there exists

such that

Proof. By definition,

By a direct computation,

so that is continuous on

.

If , then we may simply choose

. If

, then the constraint set is empty and the left-hand side is infinite, so we choose

if

and

otherwise.

Suppose . If

or

, then

identically, so that we can choose

.

Suppose instead that . Fix

. Then

is compact, so that

is closed and bounded, and thus compact by the Heine-Borel theorem. Since the sets

are also compact, we can define their extrema

At least one of these sets will always be non-empty, since and

. If

is always empty, then we can omit its discussion later on. However, if

for some

, then

for any

. Without loss of generality then, we assume both sets are non-empty for some sufficiently small

.

Using monotonicity properties, for any

. Therefore,

Now it is clear that whenever

. By the monotone convergence theorem, there exist

such that

and

Define . Since smaller sets yield larger infimums, for sufficiently large

,

Taking , by the squeeze theorem,

Finally, choose

to deduce that

Remark 1. Most arguments in Lemma 1 boils down to the compactness of , and by extension, the space

of Bernoulli distributions, as well as the relative continuity properties of

and

. Here are some proposed steps for further exploration:

- Generalise the risk functional to

, where

is a space of probability distributions that is compact under a suitable metric or topology.

- We would probably need to partition

into

compact sets, then define the compact sets

.

- During the sequential argument, we could use sequential compactness to concoct a convergent subsequence

in place of a by-default convergent subsequence. That way, we might still be able to infimise over

via

.

- Since we only care about infimising, we do not need the strength of full continuity for

; rather we would only require its lower semi-continuity property, which could be conceived as the “lower half” of vanilla continuity.

Thanks to the continuity of , we can obtain the pleasant tail upper bounds below.

Theorem 1. Fix and natural numbers

,

. Then there exists a universal constant

such that for any random variable with Beta distribution

,

Proof. Denote the closed (and thus, compact) sets and

. Use Lemma 1 to construct

such that

for brevity. Using the conjugate-prior connection between Beta distributions and Bernoulli distributions, since the sum of i.i.d. Bernoullis yield a Binomial,

where for i.i.d.

. By Bayes’ rule and the law of total probability, using the uniform distribution prior

with p.d.f.

:

In particular,

In what follows, set and follow the proof of Lemma 13 in Riou and Honda (2020) to obtain the upper bound

where using Stirling’s approximation. We remark that in the live algorithm, at time

,

would be a somewhat confusing random variable, and the tail concentration bounds are conditioned on .

Remark 2. The challenge to generalise this result comes in require concrete distributions to work with, and so our general version would need to be “simplified” into, or expressed in terms of, a more computationally tractable option. One possible area for exploration would be considering the compact set of bounded-mean Gaussian distributions

where is compact, then applying meaningful tail-bounds of the Gaussian to derive the risk version of said concentration bounds.

These upper bounds are, with more technical bookkeeping, ultimately responsible for the asymptotically optimal regret bounds. And since contiunity is a relatively benign condition, many risk functionals enjoy the tail upper bound of Theorem 1, and potentially, the asymptotically optimal regret bound for -Thompson Sampling.

Example 1. Given continuous risk functionals and constants

, the linear combination

is also a continuous risk functional. See Examples 2 and 3 for myriads of continuous risk functionals that can be combined.

However, a proper proof of the Thompson sampling algorithm requires tail lower bounds. To achieve that goal, we introduce the notion of a dominant risk functional.

Definition 2. For any , define

We say that a risk functional is dominant if for any

and

, there exists

and

such that

and . We remark that by Lemma 1, if

is continuous, then we are guaranteed the optimised KL-divergence result.

In the original version, it was this concept that I dreamt of while struggling to solve the bandit problem. I prayed long and hard, and solved the problem in my dream thrice. I was shocked, and said to myself, “I must be dreaming. I will wake up and write down my solution.” And so at 4.30am sometime in February 2022, I did just that, and after a sanity check at 8.30am the next morning, concluded that the solution was correct.

In any case, the dominant risk functional property guarantees for us a much-needed tail lower bound.

Theorem 2. Fix and natural numbers

,

. If

is dominant, then there exists another universal constant

such that for any random variable with Beta distribution

,

Proof. Fix . Since

is dominant, there exists

and

such that

and , where the last inclusion holds by

. Assume

for simplicity. Taking probabilities, and denoting

The rest of the calculation follows from the proof of Lemma 2 in Baudry et al (2021) by using Stirling’s approximation, and yields the desired lower bound

Remark 3. This tail bound eventually bounds all other terms by constants, once the exponentials cancel other exponentials out in subsequent calculations. The dream dealt with the slightly more general case , where

. I couldn’t dream of the higher-dimensional scenarios. Nor did I need to, to be very honest. See Remark 2 for the computational challenge of generalising Theorem 2 to more general forms for the theoretical use of

-Thompson Sampling.

Remark 4. The bounds in Theorems 1 and 2 work precisely for a special class of distributions, namely Bernoulli bandits (or slightly more generally, multinomial bandits). For other common classes of distributions, like Gaussians for example, we would need different tail lower bounds. Moreover, we would need to work with specific conjugate pairs of distributions, and approximate non-parametric bandits using parametric ones, which leads to messier approximation-controlling calculations when evaluating the regret bound.

But you might wonder—what functionals could pass the dominant risk functional criteria?

Lemma 2. Let be continuous and

be a constant pivot point. Suppose

is non-increasing and

is non-decreasing. Then

is dominant.

Proof. Fix and

. Use Lemma 1 to produce

such that

Set . First suppose

. Either

or

. In the former,

for

, which implies

as required. In the latter, for

, which implies

as required. If , then

is non-decreasing, and the second case holds. Finally, if

, then

is non-increasing, and the previous argument holds.

Remark 5. For two risk functionals satisfying the hypotheses of Lemma 2 with the same pivot point

and non-negative constants

such that

,

is dominant.

Example 2. Given , denote

. The following risk functionals are continuous and satisfy the hypotheses of Lemma 2 (here, let

,

have total integral

, and

denote the c.d.f. of the standard Gaussian):

- Expected value:

,

- Conditional value-at-risk:

- Proportional hazard:

- Lookback:

- Spectral risk:

- Entropic risk:

- Dual power distortion:

- Wang transform:

- Logarithmic distortion:

-Sharpe ratio:

Remark 6. Since the Sharpe ratio is not well-defined at , we do not have the nice compactness property of Lemma 1 for the vanilla Sharpe ratio. The dilation by

allows the Sharpe ratio to be defined for

. Given a

-armed Bernoulli bandit with maximum probability

,

satisfies the requirements of Lemma 1, and we recover its useful tail bounds.

Lemma 3. If is differentiable on

with non-decreasing derivative

, then

is dominant.

Proof. We claim that no matter what, will satisfy the hypotheses of Lemma 2.

- If

, then

is non-decreasing.

- If

, then

is non-increasing.

- If there exists

such that

, then the intermediate value property of derivatives yields

such that

. Since

is non-decreasing,

is non-increasing and

.

In all three cases, satisfies the hypotheses of of Lemma 2, and thus are dominant.

Remark 7. More generally, if is convex (which generalises Lemma 3), i.e. for any

and

,

the risk functional will be dominant. Furthermore, for any two risk functionals

satisfying the hypotheses of Lemma 3 and non-negative constants

such that

,

is dominant.

Example 3. Given , denote

. The following risk functionals satisfy the hypotheses of Lemma 2 (here, let

):

- Second moment:

- Negative variance:

- Mean-variance:

- Exponential tilt:

- Quadratic utility:

Furthermore, for two risk functionals and non-negative constants

satisfying the hypotheses of Lemma 2,

is dominant.

Therefore, most risk functionals as listed in Examples 1, 2, and 3 are the ones that most people care about are in fact continuous and dominant, and therefore, by passing the relevant arguments through much book-keeping, enjoy the asymptotically optimal regret bound for -TS on the Bernoulli bandit environment.

Theorem 3. The regret bound of -TS over a Bernoulli bandit environment is asymptotically optimal, and given by

Proof. Follow the proof of Theorem 1 in Chang and Tan (2022), and apply Theorems 1 and 2 in the analysis. Left as an exercise (effectively) in algebra and mildly clever calculus.

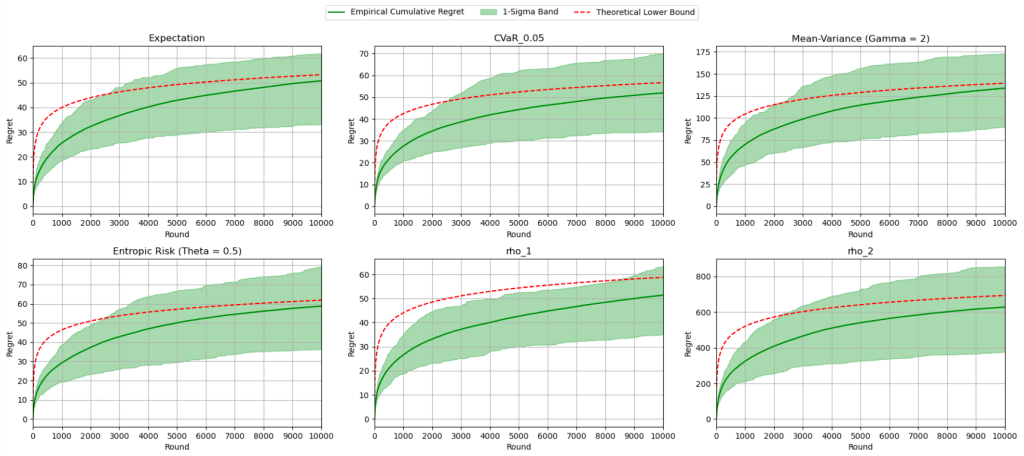

Oh, by the way, with the help of ChatGPT, here’s a Jupyter writeup of the implemented algorithm and some pretty pictures!

The red curve indicates the theoretical asymptotic lower bound, and each diagram reflects the algorithm running for a fixed -armed Bernoulli bandit, with different risk functionals, even combinations of them:

And for them all, the asymptotic lower bound lies happily in their -sigma bands. (Yes, each algorithm was averaged across

runs!)

And with that, we are truly done. Happy lunar new year!

—Joel Kindiak, 16 Feb 26, 1131H